There are tens of thousands of children and young people in America who came to the United States as babies of parents who worked in the fields, or on construction sites, or in hotels or restaurants. These kids have grown up as Americans, they are culturally American, and they have American dreams, but they have no future. In the thirty years that I’ve worked on farms and ranches around California and Oregon I’ve gotten to know some of them well. I listen to the radio and read the news and I understand the complexity and frustrations of the immigration situation as well as most, and I’m probably more familiar with the intestinal workings of immigration enforcement better than many, but I think that it is cruel, unworkable, and actually insane to talk about deporting these young “aliens” back to countries they barely know. My wish is that we Americans summon up the integrity for an honest debate what a real and comprehensive immigration policy should be, and my dream is that we welcome these kids in before we have a huge toxic permanent underclass that brings out the worst in everybody.

There are tens of thousands of children and young people in America who came to the United States as babies of parents who worked in the fields, or on construction sites, or in hotels or restaurants. These kids have grown up as Americans, they are culturally American, and they have American dreams, but they have no future. In the thirty years that I’ve worked on farms and ranches around California and Oregon I’ve gotten to know some of them well. I listen to the radio and read the news and I understand the complexity and frustrations of the immigration situation as well as most, and I’m probably more familiar with the intestinal workings of immigration enforcement better than many, but I think that it is cruel, unworkable, and actually insane to talk about deporting these young “aliens” back to countries they barely know. My wish is that we Americans summon up the integrity for an honest debate what a real and comprehensive immigration policy should be, and my dream is that we welcome these kids in before we have a huge toxic permanent underclass that brings out the worst in everybody.

– California organic farmer

::::::::::::::

A couple of Sundays ago I went on a Farmworker Reality Tour to Watsonville, CA, organized by Dr. Ann López, founder of the Center for Farmworker Families and author of The Farmworkers’ Journey. A bunch of my blogger friends at Daily Kos made the journey to the heart of one of California’s major agricultural centers to visit four different homes and “challenge us to better understand the conditions of Mexican farmworkers in Northern California by sharing in their lives, food, and living quarters.”

It was quite a trip. From leaving the Burger King parking lot armed with care packages…

through holes in the fence…

to the first home…

and the signs pointing to the harsh realities of living in poverty, exposed not only to the elements but lawlessness and violence…

My friends wrote in serious detail and heartfelt prose about the living conditions and circumstances these workers and their families find themselves in, in varying degrees of dis(re)pair.

Farmworkers Reality Tour: A Smack in the Face. – by Glen the Plumber

“President Obama, I want this country to be the leader in human rights legislation… again” – by remembrance

Wandering thru a Watsonville Migrant Camp (w/ Video) – by BentLiberal

Standing by MB with the most hated of this land (Part I) / (Part II) / (Part III). – by catilinus

In fact, I felt like they had done such a superb job at conveying our experience, both poetically and visually, of being so graciously invited into the various abodes (one tent site on the Pajaro River, one shack in a field, and two run-down houses in town) that at first I didn’t know what else I could add. But then I realized that there can never be enough stories about this forgotten segment of our population. (kind of like OWS, one afternoon is simply not enough to get people’s attention, you have to keep coming back like moles out of the ground), so I decided that I wanted to go down another path with it.

Anytime you are faced with the harsh realities of economic, environmental and social injustice, with the ones that did not make the curve in the relentless race called capitalism, you can’t help but feeling shocked, outraged and deeply touched. I think it’s actually a bit of a blessing to be confronted with those realities, because it allows you to feel your own and everyone else’s humanity, and through that perhaps begin to heal and expose some of those rifts and wounds.

That said, sometimes I find myself a bit beyond the shock and outrage, and that’s probably because where I live in San Francisco I see the kind of destitution we encountered in Watsonville on a daily basis. As we were descending into our first farmworker’s residence down by the banks of the Pajaro River, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of deja vu.

The encampment under the river canopy…

seemed so close to the encampment I walk by every day under the old “New” Mission Theater’s canopy…

The shopping cart full of spoils in the Watsonville park…

was not so far from the shopping carts I see all the time in Golden Gate Park…

Life at the bottom in rural America…

looked similar to life at the bottom in urban America…

I’m saying and posting all this not to evoke more shock and outrage, but to explain why I’m generally someone who looks towards positive signs, small rays of hope, and possible solutions to each problem, simply because I don’t need any more convincing that there is a truly neglected and systemic underclass in this country. Where I live, I could summon despair worth several lifetimes, but since I don’t think that would actually help anyone, I’m more interested in the cracks through which the light gets in (hat tip to Mr. Cohen).

It’s why I really appreciated remembrance’s post that gave a ray of hope for the many migrant women who are victims of Domestic Violence (DV).

It’s also why I wanted this post to be a ray of hope as well, because I know so many small organic farmers who pay their workers well, don’t expose them to pesticides, and some of them are able to offer the most coveted of all farmworkers’ perks, year-round employment!

So I set out to write about how all of us can create a better life for farmworkers in a huge way through the small daily acts of buying our food and produce from our local farmers.

I wanted to connect the dots between this…

and this…

and how life can improve for these folks…

when we shake the hands that feed us…

I wanted to promote a California farm that I know does great work, treats their workers with great respect and under the best possible conditions, and grows and sells some of the freshest, cleanest, most nutritious and delicious produce out there. I thought it would be great to hear first-hand from a farmer about how the current immigration policy and situation affects him, the challenges he faces, and what farmers who really care about the well being of their workers can do to create the best possible working conditions in the face of a system that relentlessly sabotages and punishes those that grow the food we eat to survive in this country.

His immediate response to my request if it would be okay if I gave him and his farm a glowing review pretty much set me straight right away…

How or where are you going to publish the essay? I’m not anxious to receive any publicity in any forum that would be reviewed by any authorities where the focus is on immigration because I am vulnerable.

He added that the immigration authorities don’t seem to care about food (although they probably eat it, I would assume), so if I were to write an essay about all the great produce he sells that would be okay as long as I don’t mention anything that goes on before the produce leaves his farm. It’s a bit like Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, and the last thing you want as a farmer is being “asked.” It’s not like there are immigration patrols combing through every field in the country, but who needs guns when someone’s livelihood can be threatened by saying the wrong thing in the wrong place …

When the migra raids someone, they’re not raiding them because they have undocumented workers — usually ICE has to drive past fields full of undocumented people in order to get to the fields they’re raiding; they raid specific targets for specific reasons, generally political in nature. It’s the nail that sticks up that gets hammered down. I don’t want to stick up, or out, any more than I already do, because I can’t afford to get hammered on right now.

The fact that a small farmer who sells his produce directly to consumers would turn down a positive review because of the immigration context the story is in shows just how screwed up things are. And with an estimated 65 percent of farmworkers being in the U.S. illegally, this is certainly not about any particular farmer, but a reality that everyone who grows food in this country is dealing with. It’s like our government’s own War on Food™ — you can eat it, but you can’t grow it. At least not with the workforce that’s willing and able to make it happen.

Having met workers on our tour two weeks ago that are being paid as little as $5 an hour for picking strawberries or raspberries, I asked him about pay and benefits, and how it might vary between small and large farms.

I’m not in a position to make an informed comparison as regards compensation/benefits between my farm and any others, large or small, because I don’t know what the compensation practices are, and there is no general rule. Some small farms may not offer much in terms of wages. Some of the large farms may have quite reasonable compensation packages; then again, many of them “offshore” the field labor to contractors, so the picture may be pretty murky and defy easy generalization.

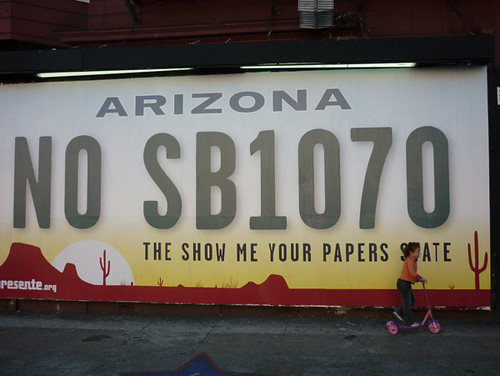

The one thing I think everyone can agree on here is that we have an immigration policy that’s completely cynical and dishonest, rooted in denial and antiquated thinking at best, and racist nativist fantasies at worst. While I do think that we as eaters of food ( yup, the 100%) can make a huge difference by supporting farmers who take care of their land and the people working on it, in order for working and living conditions of farm workers to improve and for this invisible, untouchabe underclass of people to be recognized for the backbreaking work they do, we have to adopt a more sensible, compassionate, and reality-based immigration policy.

Perhaps listening to our farmers would be a good first step in that direction…

I do think it is a good idea to focus on solutions, rather than just pointing out the problems. One solution is to work towards a year-round production program as a foundational way to improve workers’ lives, and that is what we’re trying to do at our farm. One of the many insanities of the current guest worker program that the US govt runs, the H-2A program, is that guest workers can only work for part of a year, so that the migrant nature of the work they perform is institutionalized and farms that work on a year round basis are denied the opportunity to work with steady crews. The fiction is, of course, that year-round jobs are jobs that citizens will want, but in fact, that’s simply not true. We, as a people, don’t see ag labor as being anything more than demeaning migrant labor, and our government reflects our bias in its law.

While I still believe that by buying our food from local, organic family farms we are contributing to better work conditions for immigrant farm labor (just by removing the pesticide factor), it’s clear that unless we as a nation can find the courage to tackle immigration and food policy in a reality-based and compassionate manner everyone from the workers camped by the Pajaro River to big industrial farms will continue to be trapped in this vicious cycle. There are dynamics at work here that make any kind of quick fix impossible.

However, simply reforming our immigration policy without also addressing farm and food policy will not suffice. Most small farmers don’t necessarily view the government in its current relationship with food as their friend and would rather stay in the shadows than have Uncle Sam impose insane food laws and regulations written by big ag lobbyists. It’s all a complex web of cause and effect that we cannot resolve unless we as a society fundamentally rethink our relationship to food and begin appreciating the hard work that goes into growing it. Fostering that appreciation and respect is something each of us can do, through the choices we make at the grocery store and through the dialog we have with each other.

On that note…

Here’s to remembering and honoring the people whose sweat and labor enables us to enjoy the fruits of this earth and survive another day on this planet we all call home!

o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o

Photos by Sven Eberlein

I have now read this post several times, each time appreciating it for its honesty and the truth of its words (and images). Thank you for shaking us out of our complacency and for linking “simple” matters like our daily food to the importance of fair solutions for immigrants. Very well done.

Thanks so much for the comment, Barbara. I am always amazed at how interconnected all these issues are, and how far-reaching the impact and repercussion of our food and farming choices are. I guess it makes sense: As much as we’ve engineered and manufactured our way to making food just a minimal part of our budget and our daily lives, eating is and will always be one thing we all share. If we all knew a little more about the processes by which food ends up at the store and our table I think there would be stronger calls for changing much of the process.

Next time Daily Kos should do the tour with kids! Got to get to the next generation on all of this too.

amen, sister!

great idea. I guess they’d just have to find the kind of parents and schools who would sanction a trip like that.

Sven, this is a beautiful and revealing post on so many levels. While I was reading it, I could not help but think about one of the powerful shrines from this year’s Dia de los Muertos. Here’s one thing that many of us don’t think about when it comes to our food…

aahh yes, just a perfect exclamation mark for this post! A little reflection goes such a long way.