This summer I got to spend a few days in Freiburg, a city of 220,000 at the edge of the black forest in the south-western corner of Germany, near the French border. While the reason for traveling to my native Germany was in large part to visit family and friends, the trip to Freiburg had a very specific objective: to find out more about the city that has become the poster child for urban sustainability and innovative city planning. My assignments were a photo essay for Grist and an interview with Freiburg’s Head of Urban Planning, Professor Wulf Daseking, for Planetizen. Check them out if you’re interested. But I thought I’d share some of the extra info, pics and snippets that I think give you some excellent insight into why Freiburg has earned the title of Germany’s Environmental Capital.

Awarded the Academy of Urbanism’s European City of the Year Award in 2010, Freiburg’s success in becoming one of the most livable urban environments in the world is attributable to a long-term vision that combines a deep respect for its cultural and architectural roots with an irreverent flair for bold and unconventional planning decisions.

There’s much ground to cover, so I’ve split it up into two parts. As Professor Daseking kept pointing out to me, planning sustainably is a long-term process that involves a lot of people and commitment over several generations; it doesn’t happen just because a couple of folks get together and decide to go green.

Very fittingly then, this first part will be about this sense of continuity, longevity and quality that forms the backbone of Germany’s environmental capital:

Part I: Freiburg Historic City Center – Keeping What Works

Martinstor at the southern end of Kaiser Josephstrasse in downtown Freiburg, Germany.

A Key to Ecological Design: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

Our story begins right after World War II, with almost all large German cities laid to ashes from the ravages of the war. With over 80 percent of its historic center destroyed, Freiburg decides to rebuild its inner city in adherence to its previous medieval walkable, multiple use layout. Along with Münster in the northern state of North Rhine-Westphalia, they are the only cities to do so, at the time a hugely unpopular decision.

Professor Daseking explains

Most people at the time wanted to erase the memories of the past by completely redesigning the city. In fact, almost all the other German cities bought up all the destroyed plots and built a completely new grid, that was the “modern” way of thinking.

This “modern” way of thinking of course at the time was to build a much wider and more spread out grid to accommodate the growing number of cars and trucks, fueled by a sense of expansion and progress, and leaving the old behind. (Considering the country’s recent past, the sentiment wasn’t entirely inexplicable, but it was certainly making it much harder for cities like my hometown Stuttgart that completely erased their historic core to get everything from traffic to carbon footprint under control.)

Freiburg’s planning director at the time, Joseph Schlippe, decided to model the reconstruction after the original medieval blueprint, not so much because he was an early ecocity advocate but because he saw value in keeping the old plots and landmarks intact, preserving the city’s history, identity and functionality. The move earned him much grief and derision, and he was ultimately pushed out of his job and run out of town for being much too conservative. But not before leaving behind the foundation for a living breathing ecocity: a dense, accessible, and mixed use grid based around a central tram line, pedestrian streets, and public spaces.

There’s no doubt that Professor Daseking, the current Green Party Mayor Salomon, and the overwhelmingly Green-voting Freiburg citizens’ lives have been made much easier by a conservative planning decision made over 60 years ago.

Renewal and Expansion of Things that Work

Nonetheless, much work needed to be done. In the 1950s and 60s everybody wanted to own a car and a house with a big lawn, so many families moved out into the suburbs to pursue their German dream. Sound familiar?

It wasn’t until the oil crisis in the early 1970s that a wake-up call was received, not just in Freiburg, but throughout Germany. People realized how dependent they had become on fossil fuels, how volatile this energy supply was, and there really was no need for wasting so much of it. The city responded, and in the following years a number of projects to make Freiburg into a lean, energy-efficient, and livable city were under way.

Expansion and Integration of Public Transit

Expansion of the existing tram network, including an integrated tariff system that made the use of public transit second nature to residents, as the backbone for new urban development and the foundation of a vibrant city.

Making Food and Daily Needs easily Accessible without Driving

A supermarket policy that restricted the development of shopping centers on the city’s outskirts, strengthening local inner city markets and making them easily accessible to young and old by public transit, bicycle and by foot.

Reintroducing Nature

Reconstruction of the unique “Bächle” (little creeks), a 5km system of water channels fed by the Dreisam River. Used for graywater and fire fighting in the Middle Ages but shut down and paved over to accommodate increased traffic after WWII, they were resurrected during expansion of the pedestrian district. Loved by everyone, but especially little ones. Local legend has it that those who accidentally step into one of the little streams will end up marrying somebody from Freiburg. 😉

Adding Artistic Accents and Aesthetics

The art of cobbling experienced a revival from 1970 onwards with the expansion of the old town pedestrian zone. Following a pedestrian friendly design concept, public spaces became continuously cobbled by natural stone and pebbles from the nearby black forest, Dreisam and Rhine Rivers. When you walk around downtown there is beautiful cobblestone everywhere, with an amazing variety of artistic patterns and designs.

Modernizing the Original

Formerly rundown and deserted streets like Konviktstrasse were revitalized through brandnew buildings built by different architects while retaining their original style. As Professor Daseking likes to point out, “the houses on Konviktstrasse are all virtually new, but nobody knows it.” The ease, aesthetics and accessibility of the medieval plot structure combined with modern functionality lured many suburbanites back into the city. Notice also plants and greenery intermingling with the built environment.

You Build it and They’ll Come

A common criticism of cities and why people don’t like living in them is that they’re drab, congested, dangerous, dirty, and any number of other horrible, suffocating things. Freiburg shows that it doesn’t have to be that way, that if you build a compact, accessible and beautiful city, people will enjoy living there, with a much smaller energy and carbon footprint. Freiburg also shows that if you build an infrastructure that makes it easy to walk, bike or take public transit, people will gladly get out of their cars and enjoy the fresh air.

Whether it’s getting there…

Designed as an integrated transport hub, Freiburg Central Station combines high-speed and regional train services with access to local trams, buses and cabs. A multi-story bicycle facility includes storage, repair workshop and “Cafe Velo.” Along with shops, hotels, theaters and 24 hour bars it’s a place that never sleeps.

going to work…

getting a cab ride…

taking a spin on the beer bike…

parking your vehicle…

or just chilling at a street café…

…life in an ecocity is so much easier, healthier, diverse and fun than in the distant, monotonous, and sprawling auto-centric concrete cubes we’ve come to accept as our standard idea of a city.

The Lessons

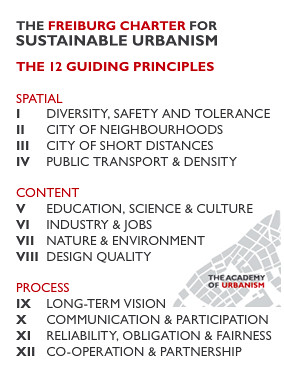

While certainly no easy task, it becomes clear just by walking around Freiburg what a big head start the ecologically-minded planners have had, by virtue of inheriting the original city layout. As I stated above, it’s not only American cities but many German cities that struggle with the implementation of the access by proximity idea because the basic foundation of their urban space promotes distance. However, there is much more than just infrastructure and spatial division that defines sustainable urbanism. Professor Daseking and his team have just recently published the Freiburg Charter for Sustainable Urbanism, laying out twelve universal principles, all interconnected and each one an important step towards the compact, sustainable City of the Future:

We have to redesign our inner cities with ecological principles in mind. Another pivotal issue will be to keep working towards social justice and economic parity. Fostering cultural diversity will be very important. And of course, education, you have to have an educated population for any of this to happen. Obviously, all these issues are interconnected, a diverse and educated populace with economic opportunity is the foundation of an ecologically balanced city. There’s a lot of work ahead for generations to come, and I’m excited about it.

We have to redesign our inner cities with ecological principles in mind. Another pivotal issue will be to keep working towards social justice and economic parity. Fostering cultural diversity will be very important. And of course, education, you have to have an educated population for any of this to happen. Obviously, all these issues are interconnected, a diverse and educated populace with economic opportunity is the foundation of an ecologically balanced city. There’s a lot of work ahead for generations to come, and I’m excited about it.

Prof. Wulf Daseking, Freiburg Head of Urban Planning since 1984

Tomorrow:

Freiburg, Germany: City of the Future. Part II: How to Build an Eco-Suburb from Scratch

The Story of Rieselfeld and Vauban and how to turn an abandoned brownfield site and military base into thriving sustainable communities.

o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o

All photos by Sven Eberlein

Great lessons to be learned.

I love this part:

I admire the beauty of the old buildings and while you would not necessarily want 13th century sewer systems, keeping true to the ways of the early residents of a city gives us important connections to our past.

When we walk the same path from the city center to the rivers edge that people hundreds of years ago did, something very special happens.

Beautiful and inspirational. I thought when reading your article that if I had been there after WWII, i would’ve probably jumped on the ‘let the old ways’ go bandwagon, too. I hope Joseph Schlippe lived long enough to see what Freiburg became. I like your philosophy that we may be coming late to the idea of Freiburg-like cities, but that we are coming. Thanks, Sven. What a lovely city to visit, photograph and write about.

Pam, while he himself probably did get to see the fruits of his labor, Mr. Schlippe never got any kind of recognition during his lifetime. From my interview transcript:

I agree, I may have also be one of the folks insisting on clearing the dust of the past and going “modern.” It goes to show that whole idea of conservative vs liberal is very subjective and can change depending on culture, era and Zeitgeist.

[…] fiction, but in fact much of it is combining ancient wisdom with modern, progressive advances. I wrote about how the City of Freiburg, Germany decided against all conventional wisdom to keep its medieval […]

[…] carbon emissions, and on and on. Instead of God’s plan I found myself more intrigued by urban planning. Soul paths turned into bike paths. Birth charts slowly gave way to Zero Drafts. As Buddhist […]

[…] example, in Freiburg, Germany, the planning director was widely ridiculed and eventually run out of town for modeling the […]

[…] Freiburg, Germany: Rebuilt after WWII with carless mobility in […]

[…] kind of a human-scale, integral transportation epoch might look like. Downtown Freiburg, Germany: Rebuilt after WWII with carless mobility in mind We're all familiar with the slogan "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle." It's a […]

[…] and skepticism as today's adopters of pedestrian- and transit-first principles. For example, in Freiburg, Germany, the planning director was widely ridiculed and eventually run out of town for modeling the city's […]