“Is this your first WUF?” is a question commonly asked at the World Urban Forum, a gathering for, by, and about city people that was first convened by UN Habitat in Nairobi in 2002 and descended on Medellín, Colombia last week for its 7th incarnation. While the answer coming out of my mouth was always either “Yes” or “Si” with a few stray “Ouis” and “Jas” mixed in, the feeling I had for most of the seven days inside the colorful pavilions spread across the Plaza Mayor Convention and Exhibition Center was one of Déjà vu, if not kinship.

After all, the question of how we are going to arrange the two percent of planetary space in which 70 percent of humanity is projected to live by 2050 in a sustainable and dignified fashion has been on my mental drafting board since before the Stone (Temple Pilot) Age. And here I found myself in the presence of 22,000 people of all ages and ethnicities, from every pocket of the world, passionate about co-creating the kinds of urban spaces that can exist in harmony with the little round ball we all call home.

No Equity, No Sustainability

The WUF7 theme was Urban Equity in Development – Cities for Life. The idea behind it seems obvious — if we invest in the most marginalized communities within our cities that are trapped behind invisible social and economic borders, everyone, including the planet, benefits.

Why? Well, it’s no secret that the default mechanism of most of our current economic and political systems rewards those who already have a lot with even more while leaving the less fortunate fighting for scraps. This generally applies not only on an individual basis, but on a municipal, national, and global level, where wealthy neighborhoods, cities, and countries add girth just by being, and poor ones can’t seem to get a leg up at all.

And yet, safe for those with the most advanced case of “I’ve got mine” tunnel vision, there are no winners in this arrangement. The haves struggle with obesity in the broadest sense of the term, from high rates of heart disease and material overconsumption to producing a carbon footprint that would take multiple planets to sustain and is lurching the one we’re on towards climate catastrophe. The have nots, in turn, are mostly in brute survival mode, without future prospects or a stake in the broader social and environmental contracts needed for humanity to preserve a livable biosphere.

This is the context within which a level playing field is the foundation for any kind of global-scale environmental improvement, including a reduction in greenhouse gases.

Riffing on the timeless “No Justice, No Peace” bumper sticker, the motto in this case is “No Equity, No Sustainability.”

Paying tribute at WUF7 to a giant of #equality and #equity

While individual acts are certainly important and international agreements badly needed, the spaces where policy and governance can most effectively meet the on-the-ground realities of people and their communities is in cities. Urban ecosystems are intimate enough to allow for meaningful solutions to be sought and implemented with respect to each area’s unique socio-cultural and geo-physical conditions, yet as a whole, large enough to make the kind of planetary impact we need if we are to curb our extractive habits.

One of the biggest lessons of assembling so many stakeholders in one place is that there is no one-size-fits-all panacea that could be mandated by just a handful of large entities and applied to everyone. While it is tempting to place all our hopes in a powerful country or head of state to flip the right switch or a big company to invent the miracle seed or breakthrough energy technology, the reality is that our global human community is a web of diverse cultural microcosms embedded within a plethora of natural ecosystems.

Diversity is the secret sauce of our planet and the source of our strength, and together we’re only as strong as the weakest, most-neglected link in the delicate chain.

The Ecocitizen World Map Project

With this in mind it makes sense that the project I was there to present with the amazing Ecocity Builders team was such a big hit at WUF7. The Ecocitizen World Map Project begins with the belief that if we all take coordinated actions towards a shared vision of sustainable and equitable development – cities and citizens in balance with nature and culture – we can address even the most serious problems facing humanity through actions, large and small alike, taken by many. Specifically, it combines education for ecological design, internet tools, data collection methods and community based research with municipal data and maps to provide a more holistic view of local urban systems and how well they are serving citizens.

Ambassador Carmen Lomellin, Permanent Representative of the United States to the Organization of American States, introducing the Ecocitizen World Map at the “Building Resilience and Equity Through Citizen Participation and Geodesign” session at the UN Habitat City Changer Room

The way to achieve such a shared vision is to enable everyone to be part of it. All too often, decisions affecting entire urban ecosystems are based only on input from those in positions of privilege, or derived from static, general data. To provide a much deeper and localized data set as well as empower residents of traditionally neglected neighborhoods to identify local urban issues and assets, the project invites those citizens to participate in a three-part survey — a general quality of life assessment, a parcel audit and household resources survey, and an environmental assessment of air and water quality.

For example, the only data usually available for a city’s water consumption is the total amount flowing in and out of the urban metabolism, with virtually no information on what happens in between. So in our pilot cities of Cairo and Casablanca, where water is precious and expensive, residents of the Imbaba and Roches Noires neighborhoods were surveyed by teams of Cairo and Mundiapolis University students (who had attended our “ecocitizen bootcamp” training events) about their specific water uses, like kitchen, laundry, or toilets. The information gleaned isn’t just valuable for city leaders to get a more nuanced view of their city’s resource flow and better understand the needs of their citizens, but it led the residents themselves to ask questions such as “why can’t we use greywater for our toilets?”

The way one of our team members described the experience, it was like holding a mirror to people’s lives, making them visible to themselves within the urban environment, and opening the door for having their voices heard.

Citizen participation in action!

Participants of the “How to use mobile technology to measure urban equity” workshop presented by ITC-University of Twente, Esri, and Ecocity Builders learning how to conduct an ecocitizen survey

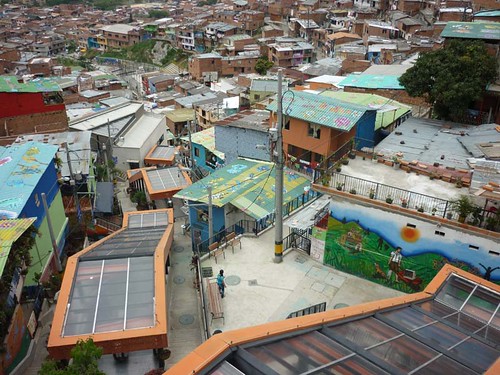

Medellín: Urban Laboratory of Inclusion

The story of how Medellín successfully used urban planning as a tool to create a more equitable and ecologically balanced city after the fall of Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel has been well documented. In fact, the very roots of the city’s turnaround can be found in a commitment by successive administrations dating back over a decade to deploy a comprehensive strategy of collaboration between planners, designers, city officials, and residents, with a strong focus on the poorest and most isolated neighborhoods. With incredible amounts of data available but not in any kind of integrated format, the first task for our Medellín Pilot was to collect all the different layers of information and present them in a clear and easily navigable map.

Putting together the map consisted of three parts: First, we went to each city department (health, education, transportation, etc) to gather all the raw data. Next, with the help of GIS mapping tools provided by our partner Esri, we built the colorful layers that allow the public to view the relationship between elements like Population Density, Income Levels, Public Transit Routes, or Green Infrastructure for each neighborhood. And finally, we integrated a layer that enables any resident of Medellín to get on the map by taking an online citizen survey, powered by crowd-mapping platform Ushahidi. Once the platform is fully developed, people in any city of the world will be able to add their insights, information, concerns, and recommendations tagged to corresponding urban elements.

EWM Projects Facilitator Ashoka Finley explains how to navigate the Medellín Ecocitizen Map at the Esri Geospatial Pavilion.

While looking at data and maps can be a powerful tool to assess how far along a city is in becoming more ecologically healthy, there’s still nothing like walking into different communities for a sensual experience of the diverse physical and cultural layers. Having spent countless hours researching various integrated development projects that have been driving the city’s transformation, I couldn’t wait to get out of the confines of the conference and into the neighborhoods. And it felt exactly the way it sounded.

You could feel the sense of pride people take in their Metro, a clean and efficient system (the only one of its kind in Colombia) that connects previously disparate “upscale” and “lowscale” communities.

Getting on and off Linea A, the main North/South line, at Estacion San Antonio.

The Metro Cable, a gondola system that has revolutionized mobility and accessibility for the poorest communities on the city’s hillsides, is as viscerally uplifting as it is visually stunning.

The Metrocable aerial cable car system has vastly improved the quality of life in Medellín’s isolated and impoverished hillside communities

The famed Library Parks, a series of public libraries strategically located in some of the most disadvantaged neighborhoods in the hillside peripheries of the city, were perhaps even more impressive in real life than in pictures. Books are just a small part of these public treasures — they really are community hubs where people come to gather, learn, and play, aided by inspiring architecture, lots of light, and green space.

A group of teenagers was practicing a dance to much laughter and joy the day I visited Parque Biblioteca San Javier.

The project that perhaps best summarizes the idea of urban equity are the “escaleras eléctricas,” a series of escalators deep in the hillsides of once-notorious Comuna 13 that enable people to climb the equivalent of a 28-story building in just a few minutes. Not only do they connect hill dwellers to vital services more quickly, but they instill a great sense of pride in residents. The community itself came up with the idea and collaborated with the city on the design that includes the beautiful orange roofs, murals, and gardens along the way, as well as music from Sinatra to the Rolling Stones humming through speakers along the way.

If this was a disadvantaged community, it sure didn’t feel that way.

- All photos by Sven Eberlein

- This is the first in a multi-part series about Medellín, the World Urban Forum 7, and the Ecocitizen World Map Project. It is crossposted at Shareable, Daily Kos, and the Ecocitizen Blog. Stay tuned for the next installments that will take me deeper into mapping magic and more colorful neighborhoods in Medellín.

I knew the posting(s) of your experiences would not be long in coming and I’ve been anxiously awaiting the first. Was just getting ready to go outside and do some yard work when this posted. Fabulous introduction of WUF7 and Medellin. (Gotta figure out how to put the mark above the i)

Your enthusiasm and optimism came through loud and clear. Let’s hope it’s the spark that lights the fire!

Thanks John, so good to know there’s some eager readers waiting for this stuff. I haven’t been too prolific in my writing, but that’s the one great thing about traveling — it really sparks the creative juices. So in a way, combining travel with work/writing is the best of both worlds, because the ink (or the keyboard) flows so freely. And I’m really rediscovering the beauty of blogging, because it allows you to just put all your thoughts out there while it’s still fresh, without having to think of the right pitch to please an editor first.

Hope you had some quality time outside today!

Oh, and as far as the í — at least on a Mac, it’s Option e, then i. 🙂

Hi Sven,

I was so glad to read about the WUF. It is hopeful to know that there are groups of people learning about urban living, while here in Flagstaff Arizona we are dealing with the first major issue of human displacement due to urban development. It sure isn’t pretty. Many on the side of the almost 200 people that may be displaced, are demonizing developers even though they previously would have said in-fill development was a priority. In my eyes, this potential development is an in-fill project. Our municipality is not prepared for this and it is painful to watch these families, some of whom are undocumented and almost all are low-income, struggle to come to terms with their probably fate, with very little assistance from the City, developers or any other entity.

I am always interested too, in hearing about urban transportation problems/solutions, so I really appreciate you writing about that.

Can’t wait to read more!

Great to hear from you, Naima, and thanks for chiming in. You’re speaking to one of the toughest issues of urban development, which is displacement. It’s the same dilemma in so many places, from San Francisco to Medellin to what looks like Flagstaff as well. I find myself in the middle on that issue a lot, but I think the best solution is for displaced residents to be offered equitable replacements.

In Medellin, for example, they are building a big Greenbelt around the city, partly to establish a place of recovery both for humans and nature, but also to curb uncontrolled urban sprawl. However, there are already some informal settlements in the way, and even though they were never officially sanctioned, how can you blame people of very little means for simply wanting a homestead? So the City of Medellin has built apartments in another part of town specifically for those people to resettle.

The problem, of course, is that often people don’t want to move from where they are, even if where they are is not even that nice a place to be and puts disproportionate pressure on the whole. Humans are such creatures of habit, and often we prefer to stick with a familiar bad habit over trying out something new that we don’t know. Fear of change! In many ways, that’s why we’ve put the whole planet in such a predicament. While I don’t like to be the one telling people what to do, I personally would welcome the offer of living somewhere that would make it easier for society as a whole to tread more lightly on the planet. Seems like the ultimate in self-interest, but unfortunately most people don’t see it that way.

The issue, in case of the community you mention, though clearly seems that there’s no equity, meaning that because these people are poor they’re just being tossed out. And it sounds like it’s probably not for some greater good, but to line the pockets of the developers. That, in my opinion, is worth fighting against.

I’d know nothing of this if it were for your telling of this encouraging news. I’m so glad I read this blog!

My heart sunk at Naima’s comment. I’ve visited Flagstaff years ago, saw drastic change taking place just south of the mountains, but admittedly do not know of the issue she raised. Meanwhile, however advantageous moving may be, don’t forget that a person may not want to severe his or her sense of place. Spiritual or emotional, some are forever tied to their birthplace. It is that same sense of place which inspires one to stand up for its protection, too.

Broad-minded nomads may feel connected to the globe as a whole, and thus can thrive in a variety of environments, but grounded natives could lose their vigor when transplanted. Such is just one of the many difficult challenges you must be facing in your work. Thank you for taking it on, and thank you for writing — in your forever entertaining style — whenever you can.

Thanks for chiming in, Ruth. Asking people to move is indeed a difficult task, and sometimes the mere suggestion may do more damage than the hoped-for results. All too often it’s the most disadvantaged communities with no other alternatives that are displaced, and it’s highly questionable whether the motivations for the displacement are truly for the common good. Naima’s example in Flag staff sounds like it’s mostly for the enrichment of a few. On a much larger scale, I’m thinking of the huge dam projects in India and China, where literally millions of people got kicked from their land, with none of the benefits promised by the dams.

But sometimes the common benefits of an eminent domain decision can really outweigh an individual’s loss. (of course, never in the eyes of the individual affected by it). But without some sort of mechanism to rearrange human settlements there would never be a new public transit line built, and I think we can all agree that that is something we’ll need more of if we do indeed want to reduce the amount of emissions from automobiles.

Thing is, human beings are pretty resilient and adaptable, it’s part of our strength. So I think that as long as the proposed structural change is supported by a vast majority of a constituency and there is an equitable compensation or alternative residence offered to individuals who will have to move, it’s a situation that can be turned into something positive for everyone.

The other side, of course, is that we are creatures of habit, and those habits and customs are what creates our identity, culture, and a lot of the great things humans do. It can be traumatic to be forced out of our comfort zones, but especially in the case of bad habits, which we have so many of and that end up spoiling the nest for everyone, we really have to try to force ourselves to think more globally. It’s simply not possible at this point in history, with 7 billion humans on pace to destroying the very planet we depend on to live, for everyone to stay in their own comfort zone that they’ve gotten used to.

In either case, I think it’s a good and important discussion to have, and I think the best solution is hardly ever the extreme on either end of the discussion, but a nuanced look at each case, with all stakeholders involved in the process.