As the rescue efforts at the Fukushima plant continue to stumble and fumble along, the discussion about nuclear energy has been in full swing around the globe. The week after the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the Swiss government suspended plans to replace and build new nuclear plants pending a safety review. In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced a three month moratorium on last year’s decision to extend the life of the country’s 17 nuclear power stations and ordered a temporary shutdown of several of its older plants. Even China, with some 26 nuclear reactors under construction a country far from skittish when it comes to generously placing its energy eggs into the nuclear basket, suspended approval for all new nuclear power plants until the government can issue revised safety rules.

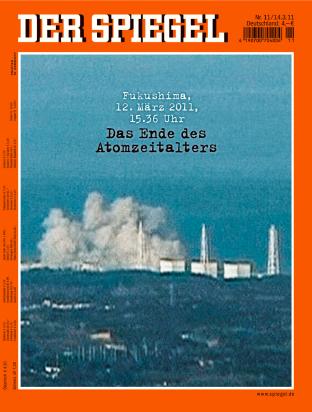

Der Spiegel, 3/14/11: Fukushima, March, 12th 2011, 3.36 pm – The End of the Nuclear Age

To be sure, these decisions did not go unchallenged. In Germany’s case, Angela Merkel’s reversal was called an embarrassment, a ploy to placate voters, and was awarded the World Championship of Hysteria. Short of accusing her of a lack of those oft-cited oval testosterone-laden parts of the male anatomy, Merkel’s move to review safety procedures in German nuclear plants was being caricatured by much of the more manly international press as that of an “Angsthase,” a fear bunny. One article entitled Germany Cripples Itself with Nuclear Angst by Spiegel Online editor David Crossland, an Englishman born in Germany, accused Merkel of pandering to irrational fears and even went as far as psychoanalyzing Germans as an “inward-looking, shelter-seeking forest nation, with a tendency toward the parochial.”

Chancellor Merkel’s center right CDU party then got hammered at the polls last Sunday in the state of Baden-Württemberg, not for deciding to shut down 7 plants, but for the appearance of political opportunism. In conservative Baden-Württemberg, the Green Party, the only political party that has consistently and unequivocally favored a phase-out of nuclear power since its inception over 30 years ago, took 24.2% of the vote and knocked the CDU out of power for the first time in 58 years, making Winfried Kretschmann the first Green prime minister in the state.

So what is it about us Germans and our irrational fear of nukes? What makes us so wimpy that we would stage a 45 kilometer-long handholding protest of a perfectly well-functioning nuclear plant? Why are my people — heralded the world over for their impeccable engineering skills — so fickle when it comes to trusting our own ingenuity with nuclear power?

There are, of course, the usual explanations. The psychological scars of a devastating war, with its lingering lessons from our grandparents that if you play with fire you’ll get burned. Being at the epicenter of the Cold War, Cruise Missiles and Pershing II’s pointed at us, one false alarm or trigger-happy Superpower-leader away from annihilation. And yes, Chernobyl, the little accident that could have only happened to those negligent and tech-challenged Russians but sent a radioactive cloud our way nonetheless. I was 18 at the time, but it feels like it was just yesterday. Sure, walking off the field in the middle of your soccer game because of radioactive rain is memorable. And naturally, sitting in the basement with your teenage buddies, pondering a slow and creeping decay of your body, leaves a lasting impression. But that’s not the whole story.

Supporters of nuclear power often cite any number of things that kill many more people than nuclear plants as evidence of our irrationality: Smoking, air pollution, walking, eating greasy food, earthquakes, tsunamis, you name it. It’s the same line of reasoning that often comes up when someone is uneasy about getting on an airplane. We’ve all heard it before: “Don’t you know that you’re x times more likely to die in a car accident than a plane crash?” From a cut and dry Vegas-style odds-on perspective, this kind of statistical risk assessment makes sense, and one would think that we über-stoic Germans should be much more freaked out every time we get in our Porsches and BMWs than by our statistically safe reactors. But we’re not. Instead of quitting our deadly driving habit, we speed down the Autobahn at 180 km/h, and the only time we get a sinking feeling in our stomach is when we fly past the roadside reactors at Biblis or Neckarwestheim.

Nuclear Plant in Neckarwestheim

On a personal level it has to do with control. You obviously don’t have to be German to relate to the idea that there is something reassuring to have your own hands on the steering wheel, no matter how bad your odds are. It also helps to have a basic understanding of the technology you’re using, and the risks inherent in it. While the consequences of technical malfunction or human error in a car accident can be deadly, the impact, albeit tragic, is quick and local. In an airplane, the unknowns — at least from a layman’s perspective — are much greater, and the stakes much higher. Who among us has never wondered during turbulence how many flight hours the captain has logged and whether everyone on the plane maintenance crew did their job diligently? However, nothing seems as removed from our personal reach and knowledge with as broad of a potential threat on all of our lives as nuclear technology, whether it’s used for energy or weapons.

As the ongoing tragedy in Japan shows, when it comes to nuclear reactors and their potential dangers, we’re completely in the dark. With each passing day, the roofless buildings reveal themselves to be labyrinths of ever more tangled complexity. Explosions aren’t this disaster’s climax but conduits for potentially more worrisome chain reactions. Sizzling cocktails of Uranium, Cesium, Plutonium and other -ums are competing for most insidious element, until we learn about mixed oxides, or mox. Spent fuel rods, stored in pools outside the unbreakable (until it breaks) containment shell, turn out to be just as radioactive as the active ones. Experts know what’s happening until they don’t. Radiation levels are low until they’re higher. Japanese officials say 20 kilometers is safe, Americans say 50. One day the alert level is closer to Three Mile Island, the next it’s closer to Chernobyl. Did Chernobyl kill 56 or 985,000 people? A week into the disaster, authorities were anticipating months of radioactive releases. Or was it years? Wait, what’s the half-life of Cesium-137 and Strontium-90? You get the impression that being rational is not enough in order to grasp what’s actually going on at Fukushima Dai-ichi. You have to be a nuclear physicist, and even they seem to be making it up as they go.

The Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant – Bulgaria 2001, photo courtesy Ed Kashi / VII

So yes, my fear of nukes is irrational, because for it to be rational I would have to be able to calculate the exact outcome of a worst case scenario. Let’s say all of the 11,125 spent fuel rods stored at Fukushima Dai-ichi were to melt down. What consequences would that carry, rationally speaking? The truth seems to be that nobody really knows how all these different links in this highly convoluted and explosive chain are going to react. How long have the fuel rods been exposed? How big are the aftershocks? Are there cracks in the pools? Are the emergency workers stuffing the right holes? Which way is the wind blowing?

To be fair, nothing in life beside our impermanence is certain. But with nukes, to extrapolate from early 21st century philosopher Donald Rumsfeld, the unknown unknowns are on steroids. It is true, as many proponents of nuclear energy point out, that the same can be said about other sources of energy like coal and oil, with their creeping side effects of pollution and climate change. And I agree. With ice caps melting and sea levels rising, getting into an accident is increasingly looking like one of the more inconsequential risks of driving our cars. But rather than pitting one insanity against another, wouldn’t the most sensible thing be to call the bluff on our collectively adopted myth that we can keep borrowing ever more energy from our planet through increasingly complex methods to feed an economic system based on perpetual growth?

This is where the German teenager’s irrational fear of being invaded by an invisible, odorless radioactive cloud from distant Ukraine morphs into the sober realization that the cheap and easy energy emperor wears no clothes. What’s crazy is not my people’s atom phobia but the idea that our planet could sustain our irrational model of constant growth and consumption. There’s an understanding that the tears are shed for much more than one’s own little skin, that the roots of the pain go much deeper than mere self-preservation. For when examined, the fear of nukes bears a message that’s as straight and direct as it gets: The pursuit of unlimited energy, mobility and prosperity is the real illusion.

o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o

I’ve sat at the table with environmentalists — ones who fight the good fight every day — in complete shock over an increasing acceptance of nuclear power. “It really is a clean alternative,” I heard one women say. I was in such disbelief I couldn’t speak. Not because of the words, but because of the mouth it was coming from. Thousands of years of toxic waste, and she called it clean.

Will we ever be able to think beyond the short term? How long will it take before every policy in place is nothing more than a knee-jerk, moratorium reaction to giant, short-sighted mistakes? Or has that already happened.

It’s raining today at my Pennsylvania home. Normally I would cherish the life giving watering of the garden, but today I suffer an irrational sadness as I wonder just what else is falling from the sky.

So true, Ruth, the idea of clean nuclear is strikes me as rather strange. I do understand that it is going to be part of the equation for a while to come, whether we like it or not, so I agree that we need to make it as “safe” and “clean” as possible. But it’s not a sustainable solution, just as coal and oil aren’t either, so we should stop treating it as such. If we don’t at least start thinking about fundamentally changing our economic system, it won’t matter which source of energy we deem less harmful, because the reality of “non-renewable” will hit us whether it’s oil, coal, gas, or nuclear.

Wow, Sven. Powerful ‘essay.’ I hope your wisdom is shared around the world.

Thanks so much, Pam, and thanks for linking to it on your blog. I posted this one on daily kos as well and it got over 250 comments. This topic really hits a sensitive spot for many people across many spectrums.

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2011/03/31/961797/-The-Irrational-Fear-of-NukesA-German-Perspective

that’s great! keep on keepin’ on, friend.