The desire to create comfort and security for ourselves probably counts as one of the most rudimentary motivations in the human reservoir of instincts. Building a safe nest is one of the impulses that not only transcends cultural boundaries but connects us to most other species on the planet. As a basic principle, wanting the very best for ourselves and even better for our offspring is as relatable as it is admirable, to the point of being socially awkward to desire otherwise.

And yet, within the context of modern society, the lines of what constitutes a fulfilled life can easily get blurred. The simple need for a roof over our heads and food in our bellies alone is already dependent on a complex industrial process, and few of us are aware of the amount of energy, resources, and logistics that goes into the beds we sleep in or the meals we consume. Things get even trickier once our basic needs such as access to clean water, food, and shelter are met and we are presented with a seemingly endless array of choices to “improve” our lives.

Avenida El Poblado, a street full of development.

Part I of this series about my adventures with the Ecocitizen World Map Project at the Seventh World Urban Forum in Medellín, Colombia explored the meaning of “equity” and how a level playing field must be the foundation for any kind of global-scale environmental improvement. In this second installment I’d like to flip the mirror and look at the other end of the spectrum, at concepts like “development” or “progress” that invariably come up when considering the turf upon which this level playing field should be built.

A Day in a Less Developed Life. Parque Biblioteca España, Medellín.

What is Progress?

If life were a competition to attain the most material possessions or the biggest name — as is often posited by the marketing industry — the #1 regret of the dying would surely be the failure to have accumulated more stuff or gained more influence. However, as most of us would probably intuit, those ambitions don’t make the list at all. It seems that what people ultimately want out of life once they drop their survival armor are softer, less outwardly measurable qualities like authenticity, friendship, time with loved ones, or a sense of belonging.

I was struck by this paradox on my very first night in Medellín, right after the cab driver had dropped me off at the spacious apartment our Ecocity Builders crew was sharing in the upscale El Poblado neighborhood. As my friend and colleague Kirstin and I were walking the half mile or so along Carrera 46 to get some food and drink at the only nearby place to do so, a big box-type supermarket, we were immersed in a cloud of exhaust that made my eyes burn.

See where we can cross the street safely? Me neither.

I thought that perhaps there were some less trafficky residential streets we would discover as we became more familiar with the neighborhood. But alas, it turned out that for the next ten days this would be our only option to get food or drink. No nearby corner stores, no side alleys to sneak through from our cul-de-sac, no bushwhacking. Sure, we could have taken a bus or a taxi, but with all the congestion it would have taken longer than walking — and missed the larger point: Shouldn’t a half mile trip to the grocery store be doable without the help of exhaust-spewing, 3000 pound metal boxes that cause everyone who isn’t inside of them to cough their lungs out? Is this what we really mean when we envision “development?”

Compare that to my first impressions of one of Medellín’s “less developed” neighborhoods a couple of days later. As I got off the Metrocable Linea K and walked into Santo Domingo Savio, a low income barrio in the Northeastern hillsides of the city, the air was clear and the noise limited to people talking and dogs barking.

Being old-fashioned in Santo Domingo.

Don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t all that horrible living like kings and queens for almost a fortnight. Our apartment had everything you’d expect from a penthouse in the good part of town, the stuff you find on the usual dream-come-true wishlists — hot tub, pool table, doorman, and all. But you couldn’t help but feel a bit trapped in there, as it seemed so disconnected from its surroundings. The fact that our default mode of transportation to get to the World Urban Forum at Plaza Mayor or anywhere else besides the supermercado was to hop in a cab felt like the kind of involuntary surrender to bad infrastructure that so many of us in the “civilized” world are forced into.

Me being me, I wanted to fully experience the ecosystem we were in on foot, no matter how inconvenient, in order to make an intimate connection with the habitat I was in. Whenever we didn’t have an early morning workshop I opted out of the taxi ride and walked to either the Aquacatala or Ayurá Metro stations. It was about a 30-40 minute walk downhill, mostly trying to find creative ways to cross car-filled streets, but also with a few stretches of reprieve from the relentless traffic leading past rows of villas hidden behind tropical greenery. To say these communities were gated would be an understatement.

Living like kings in El Poblado.

Meanwhile in the mean streets of Santo Domingo, people seemed strangely undaunted by having their most prized possessions spread out in the middle of the street. As I was meandering through the windy streets and alleys of the community, I saw families playing board games on the sidewalk in front of their house, people gathered around the carts of small vendors offering fruits and other snacks, and kids playing catch or kicking the soccer ball around. The homes looked simple and close together, which seemed to not only make for adequate living quarters but be conducive to spontaneous interaction and a natural community feel.

Suppose I was a first-time visitor from another galaxy in the market for a new home on distant planet Earth, without any prior knowledge of human idiosyncrasies in regards to wealth and status. I don’t think anyone would blame me, given these short reconnaissance tours, if I were leaning toward putting down roots in Santo Domingo. And yet, the predominant notion of progress among current residents of this planet looks a lot more like El Poblado than Santo Domingo.

What is it that makes us humans — creatures whose highest cultural expressions are saturated with cries for love and connection — want to live isolated lives behind walls, wheels, screens, and fences?

How to measure “Quality”

Invariably, any time one questions progress as it is understood in the modern material context, critics point to the great accomplishments of development — the raised standard of living, health, life expectancy, opportunity, mobility, etc. “Nobody wants to go back to living in a cave” is an oft-heard defense of development at all costs, a savvy rhetorical tool to keep the archetype of western materialism lodged in our collective imagination as the best and only way forward, and a less resource-intensive life as going backwards.

The reality is that measuring what truly constitutes a good life in any sort of universally applicable way is a tricky undertaking. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has long been the main indicator for a country’s overall standard of living, but there’s an increasing question whether the excessive focus on the creation of material wealth serves the ultimate objective of enriching human lives. The UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) thankfully goes beyond the “everyone just wants to make money” assessment by measuring development through combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income, even adding in adjustments for inequality.

But how do you account for those special moments that don’t require any money or degrees? The playful interaction, the random act of kindness, the gentle touch? Are they just the cherry on top of all the tangible physical stuff, or is there a point after our basic physical needs are met at which they occupy a much larger territory in the chart of human aspirations?

A moment in San Javier that didn’t make the charts.

Even if we pretended for a second that money and material possessions are the primary indicators by which to determine quality of life, the numbers don’t always add up.

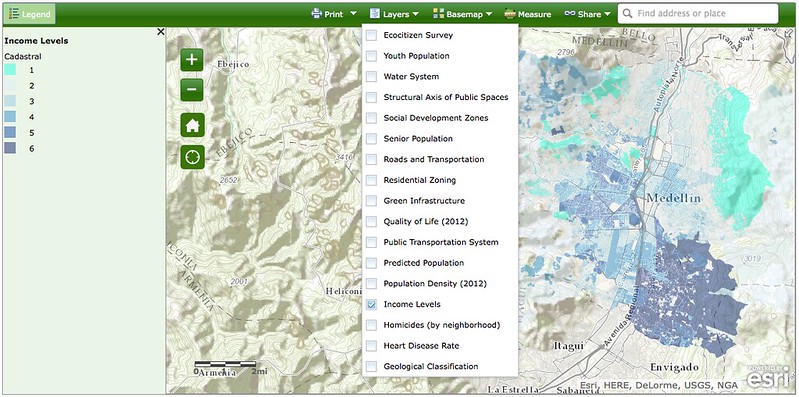

Take our pilot city Medellín, for example. Thanks to the Ecocitizen World Map team’s collaboration with the City of Medellín who provided us with extensive demographic data sets that we were able to integrate into a powerful GIS map with help from our partners Esri and The Institute of Conscious Global Change, we were able to come up with some visual clues that contradict the “more stuff = better life” formula.

If we pull up the layer with Medellín residents’ income levels, we find that the richest areas represented in dark blue are in the city center and the Southeastern part of town, including El Poblado. The lowest income areas are in the North, with a huge turquoise splotch signifying the very poorest neighborhoods in the Northeastern hills, including Santo Domingo.

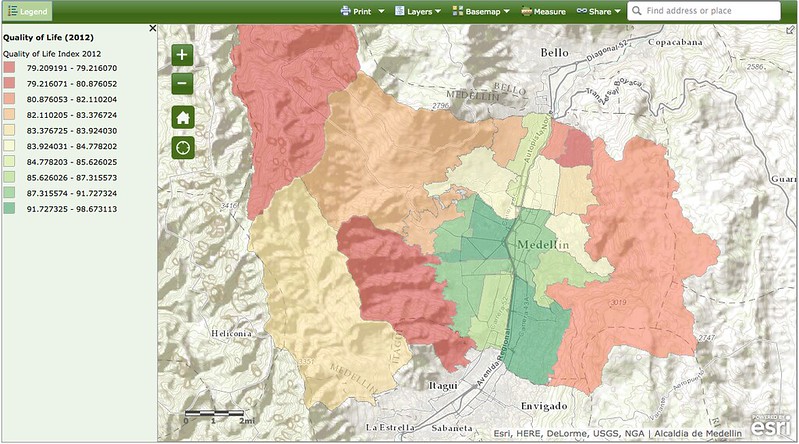

Next, let’s look at the Quality of Life layer culled from data provided by the Department of Planning. Not surprisingly, the highest indices (in dark green) are found in the center and south where income levels are high.

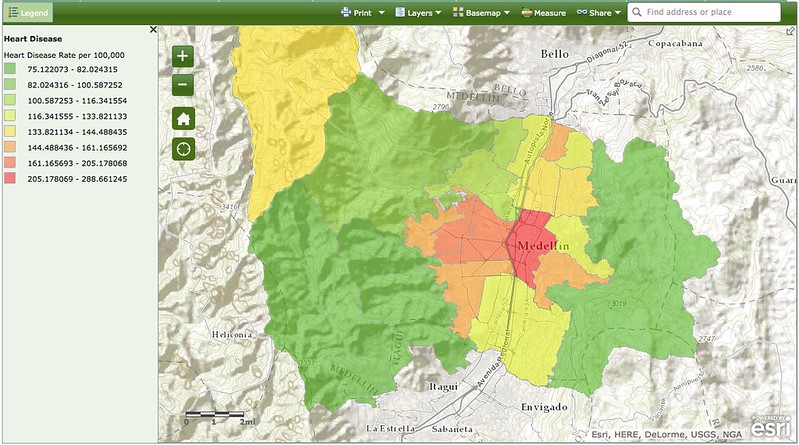

Now take a look at the heart disease rates. They run almost completely opposite to the Quality of Life map, meaning the higher your living standards the higher your chances of suffering from heart disease at some point in your life.

Go ahead, give it a spin and select some of the other layers…

(if a layer doesn’t show up, try to zoom in)

While no absolute correlations can or should be derived from this information, organizing the raw data through these GIS mapping tools provides the kind of visualizations that enable people to gain better insights into their own cities and neighborhoods, use the information to think about the broader context within which they live, and become advocates for improvements based on that information.

In this case, the idea that the comforts of more sedentary lifestyles might have negative effects on our cardiovascular system is not exactly breaking news, but I found it useful to see my personal observations reflected in the data. Likewise, for citizens of Medellín going about their daily routines, this kind of visualization is like a mirror: a way to “see” what they look like as a system, to connect dots that might otherwise be less visible, and to become empowered as a community to define a vision for their version of an EcoCity.

Medellín Metro: Preventing heart disease by going about daily life on foot.

So… are we better off being “better off?”

As one might expect, the answer to this question depends on the lens(es) through which one is looking. Pondering this question myself, I find it helpful to filter it through a global as well as a personal frame, then draw the connection between the two.

The Global Frame

From a (human-centric) global perspective, the concept of development as viewed through the western material peephole has undoubtedly done good things for large segments of the human family. From the invention of the automobile and industrial agriculture to modern medicine and information technology, we have made things possible in the blink of an eye that would never have been thought possible just a handful of generations ago. Life has become easier and less unstable in many regards thanks to a vast industrialized fossil-fueled infrastructure, at least for those born into places that have received the lion’s share of the material benefits.

The other side of the equation is that the ecological footprint of humanity as a whole now demands 1.4 Earths, and if all humans were to consume at the level of the most developed nations it would require five planets to sustain everyone. Since we don’t have five planets, it means that we’re on a rapid trajectory to deplete the one we do have. In other words, the cost of all this development and the commoditization of nature has been charged on the planet’s credit card while pretending there’s no credit limit — and we all know how that usually ends.

It seems reasonable to me that the looming bankruptcy of the very ecosystem that all of life on Earth depends on should not only outweigh in importance the accumulation of more borrowed benefits (at least the most gratuitous ones) but be at the core of any serious deliberations about the meaning of progress and development.

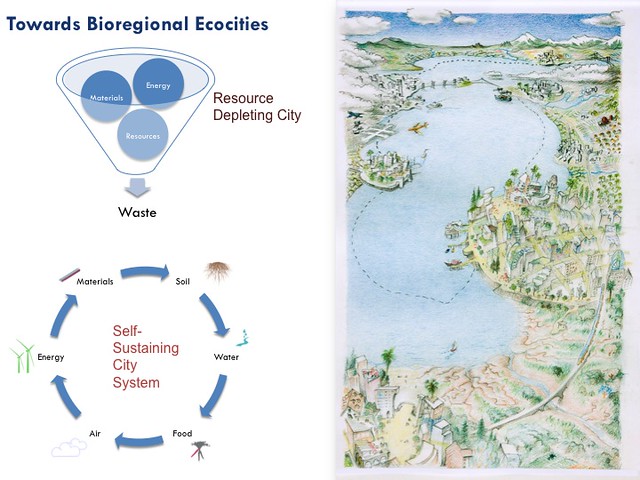

Treating cities like natural metabolisms would enable us to get by on one planet. Graphic by Ecocity Builders.

The Personal Frame

From a personal perspective, a lot of the same benefits of the industrial mindset apply. It’s undeniable that the materialistically-oriented philosophy of development has done much to improve many peoples’ personal lives (though we should also not forget that it is often at the expense of others in faraway lands or on the other side of town whose resources are disproportionately extracted and who suffer disproportionately from the outsourced pollution – see Part 1 of this series).

Whether it’s the privilege of driving to a store to buy a banana grown half-way around the world or the ability to instantaneously share our thoughts with anyone in the world through multitudes of machines connected by powerful (and power-sucking) cyber networks, there’s no denying that the ease and convenience built into the archetype of a developed life is challenging to argue against, at least within the western material frame.

Typing slow, living large. La Carrera Carabobo.

And yet, part of the allure of this “better life with more things attained more easily and quickly” is also its fallacy — that it comes with little or no cost. As mentioned above, the most consequential price we’re paying for our slavish devotion to physical growth as the path to happiness (while conveniently externalizing costs like loss of biodiversity, resource depletion, soil erosion, pollution, or climate change) is the wholesale destruction of the only planet we have.

But even if that is too broad a scope, there are individual costs that don’t ever make it onto the shiny billboards. Getting struck by a car, ingesting toxic chemicals, or suffering from heart disease are but a small sampling of the physical downsides of the highly industrialized lifestyle. Stress, loneliness, and depression only begin to describe the psycho-spiritual toll it can take.

Objects of desire in places that are quite alright. View from Metrocable onto the roofs of San Javier.

So are we better off being “better off?” Obviously not a simple yes/no question, but the evidence is mounting that the costs of our material pursuits have already surpassed their benefits. Just as there is only so much food you can eat before it’s not healthy for you anymore or so many things you can own before things don’t mean much anymore, there’s only so many resources we can extract and burn and throw away before the planet’s fragile ecosystem can’t recover anymore.

There is certainly development that makes sense and is the kind of development that the dwindling resources still available to us should be invested in. The Metrocable, built by the City of Medellín to connect its poorest neighborhoods with downtown, is a great example of investing in projects that improve people’s lives without adding any of the pollution, congestion, and waste often associated with such endeavors.

Sustainable development: Metrocable Linea K going to Santo Domingo.

But the time has also come to think about development and progress outside the material scope. Nobody in good faith could claim that the purely industrial notion of progress that has been the dominant paradigm for the past 200 or so years has left the planet’s ecosystems in better shape. Trusting that somehow the very Modus Operandi that has us running up against all kinds of carrying capacities will get us out of it is a bit like the Einstein quote about doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Or as Charles Eisenstein writes in his recent essay, Development in the Ecological Age, “there aren’t enough resources on earth for every human being to live like a North American or Western European.” In all honesty, there aren’t enough resources on earth for every North American or Western European to live like a North American or Western European anymore.

Can we shop ourselves out of this crisis? Centro Comercial Monterrey, El Poblado.

Give Happiness a Chance

The only way I see out of this mental one-way street to ecological bankruptcy is for humanity to redefine the meaning of development, the meaning of progress, the meaning of success, the meaning of happiness.

The good news is, we already know that life is about so much more than accumulating stuff and getting from Point A to B as quickly as possible. We say it and live it all the time, whether it’s at official functions like commencement ceremonies, weddings, funerals, or houses of worship, or during countless moments of simple connections that we make happen every day. The love, the joy, the play, and the learning from each other, but also the shared grief and moments to lean on each other, don’t require any “thing,” and as mentioned in the beginning, are on top of people’s “life wishlists” whenever they allow themselves to speak from the heart.

Even better news is that there is already an index that takes a holistic approach toward notions of progress and gives equal importance to non-economic aspects of well-being — Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH). Comprised of four pillars — good governance, sustainable socio-economic development, cultural preservation, and environmental conservation — that are further classified into nine domains of well-being — psychological well-being, health, education, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards — GNH offers a dynamic accounting of human needs that more closely reflects the full scope of our existence.

Working on being well. Girls choreograph their own dance outside Parque Biblioteca San Javier.

In many ways, the Ecocitizen World Map is an attempt to project the values and metrics of Gross National Happiness onto an urban canvas. Integrating the physical conditions of cities into the social and cultural fabric of its citizens within a broader bio-regional context is not only the most honest way to assess the true greatness of a place, but also the most sustainable one.

However, it comes with a warning: Taking a more holistic approach to what it means to have a vibrant, healthy, beautiful, and regenerative city may turn our current understanding of progress on its head. It may even make the less developed part of town seem more attractive.

At least for someone visiting Earth for the first time.

Poor San Javier looking like an EcoVillage.

###

- crossposted at Shareable & Ecocitizen Blog

- All photos by Sven Eberlein

- Part 1: Postcard from Medellín: A Big WUF for Urban Equity

- Sven is the Ecocitizen World Map Project‘s Community Liaison

- Connect on Twitter and Facebook

As I reflect on my globetrotting endeavors it’s not any 5-star hotels or fancy restaurants that stick out in my bank of memory cocktails (and I didn’t frequent either often) but it is the 5 cent room in Nepal where my wife and I sat around a camp fire and interacted with the neighbors at the top of the memory bank.

But during those travels and while living in third world countries I witnessed the yearnings to emulate the West’s consumptive lifestyle and the realization of it being largely accomplished in many locations. And each time I concurrently witnessed a breaking up of the fabric of the human bonds of connection. It was hard to call what I witnessed progress.

Excellent, well-presented and insightful discussion of a very important aspect of modern living.

Thank you for the kind words, Sir.

I think that it’s important to not present it as an all or nothing proposition, as both worldviews have good things to offer. In fact, it’s the all or nothing proposition that usually makes people defensive and closes their minds to certain good aspects of another way of being they might be missing. But I think that generally-speaking, the western material way gets much more press and promotion, in all parts of the world. In the U.S. it gets trumpeted to keep feeding the Ego about being “the greatest nation on Earth,” and in developing countries, as I wrote here, the appeal to want to be and consume like the people in “the greatest nation on Earth” is powerful.

So I think we could really use a little more balance, and that means that we in the supposedly “greatest nation on Earth” could actually learn a lot from the “inferior nations on Earth.” They have a lot of things to offer that our money can’t buy.