This is Part 2 of my trip last week to Vancouver, B.C. to meet up and exchange ideas with some of the leading thinkers in sustainable urban design and planning. (Carless in Vancouver, Part 1: Boots on the Ground described the first two days commuting between my Mount Pleasant neighborhood digs and the convention center to attend presentations about leading practices in resilient urban systems by ecocity pioneer Richard Register and sustainable developer John Knott.)

Specifically, I was there to discuss the International Ecocity Framework and Standards (IEFS), an initiative currently being developed by Ecocity Builders and an international committee of expert advisers that seeks to provide an innovative vision for an ecologically-restorative human civilization as well as a practical methodology for assessing and guiding progress towards the goal. As the UN is beginning to recognize the important role of cities and local governments in sustainable development — reflected in the Rio+20 Earth summit draft agenda — the need arises for transparent, verifiable and measurable indicators to track progress as cities and citizens move towards increased balance with living systems.

I know, that’s quite a mouthful. Measuring something as complex as entire urban systems can be quite the noggin buster, so let me just say, I feel your pain!

And let me also say this up front: When you’re looking to fundamentally change the unsustainable fossil-fueled structures upon which modern life hinges (rather than just tinkering around the edges with a little “Green” here and there), you not only run into much doubt and fierce resistance (including doubting yourself from time to time), but the harsh reality of how deep a hole we’ve dug for ourselves. For example, the City of Vancouver, often touted as one of the greenest cities in the world, has an environmental footprint of almost four times the sustainable level, meaning if everyone on earth lived as Vancouverites do today, we would need three to four planets to support that level of consumption.

As I was roaming through Vancouver on the lookout for ecocity indicators, the reality of this footprint was reflected in many places. Despite Vancouver’s many successes in sustainable urban planning…

it quickly became apparent how far this metropolis still is from being an ecologically healthy city.

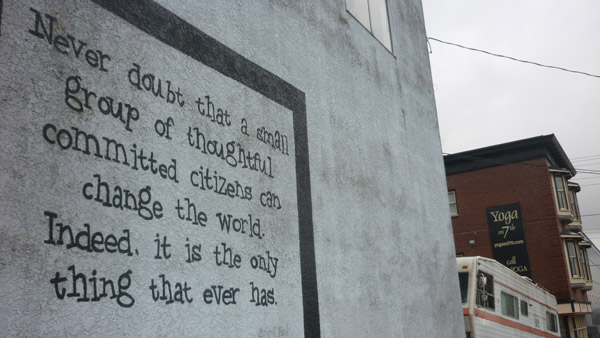

I was blessed to be able to spend time with some of the local visionaries who’ve been instrumental over the last 30-40 years in getting some of the EcoDensity principles implemented in developments that are today celebrated and held up as Vancouver’s finest. A common chorus was that none of it would have happened without the passionate activism and unflinching determination by a small group of visionary citizens who saw what was possible and insisted on making it happen, despite what most city officials and the planning establishment thought of the idea.

It is thus that I continue my journey through Vancouver with the full awareness that ecocities in their full manifestation currently do not yet exist anywhere on planet Earth, but, that without a clear vision of the multidimensional changes needed and a determination to work towards those changes our best intentions will do nothing more than put a green veneer on a structurally flawed foundation.

People say we should develop models that go for the low-hanging fruit. I say, let’s go for the high-hanging fruit. Leave the low-hanging fruit for the children.

– Richard Register

Ecocity Builders founder Richard Register celebrating the Jane Jacobs-inspired South Falls Creek Village in Vancouver.

Thursday, February 9th

From Neighborhood Power to the Power of Neighborhood

We have to value the people in our society and organize around their capabilities

– John Knott

The workshop at the BCIT’s School of Construction and the Environment‘s downtown campus wasn’t scheduled until 1pm, so I decided to check out the Neighborhood Energy Utility (NEU), an environmentally-friendly community energy system that has been providing space heating and domestic hot water to all new buildings in Southeast False Creek (SEFC), including to the Olympic Village, since the 2010 Olympics.

Instead of walking through the quaint Mount Pleasant neighborhood streets to get to the south end of the Cambie Street Bridge where the NEU is located, I decided to head straight down the hill and detour through a more industrial part of town. I don’t know if it’s because there are fewer people roaming the streets or because their facades aren’t manicured for public viewing, but there’s something about the less residential areas of a city that I find strangely appealing.

It’s the part of the city that feels less guarded and rehearsed, the place one goes to scream and to cry, revealing the struggles and contradictions of the human condition and the shadows of our own creations in its raw and unkempt glory. It’s where the apex of civilization meets the hole in our heart and our collective soul emanates from the spaces between concrete and power lines.

I turned right on Cambie Street, walked past the Olympic Village skytrain station, and followed a wide path that disappeared underneath the southern end of Cambie Street Bridge and dead-ended in what could only be construed as — what else? — a Neighborhood Energy Utility.

It’s the first utility of its kind in North America. In a nutshell, the energy center recovers raw sewage from the urban wastewater system underneath city streets, and through a heat exchange process captures thermal energy that is then delivered in the form of hot water via a pipe system to approximately 6,600 units (over 10,000 people) in the Southeast False Creek neighborhood.

By providing about 70% of the neighborhood’s annual energy demand (solar thermal modules and efficient natural gas boilers make up the balance), the NEU eliminates over 60% of the carbon emissions associated with the heating of buildings. And speaking of buildings, the center itself as well as all the energy-transfer stations are LEED™ certified, their high quality design and hot water radiant heating systems further reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions normally associated with power plants. For the techies among you, here are more specs. For the more visually-inclined, here are a couple more perspectives…

Time was flying and my stomach was growling. I hopped on the Canada Line and got off at the City Centre Station, where I munched on some yummy Pad Thai at one of Vancouver’s countless Asian restaurants, making it to the 6th floor of the BCIT campus just in time for the IEFS workshop. It was quite a conglomeration of luminaries that had gathered: Representatives from the City of Vancouver, Metro Van, industry, and real estate, as well as LCA experts and people like Gordon Price, Vanessa Timmer, Bill Rees, Sebastian Moffatt, and Jennie Moore.

Ecocity Builders Executive Director Kirstin Miller gave a brief update on the current blueprint of the IEFS, and the 15 conditions that would need to be addressed in order for a city to achieve basic “ecocity” status.

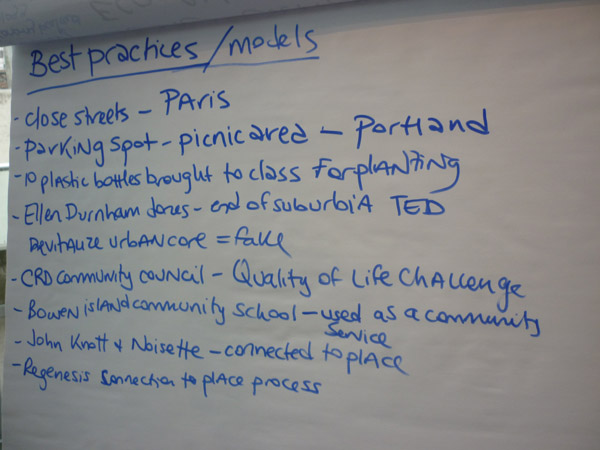

Next, we split up into 5 groups. Table 1 had the entire City of Vancouver crew ecocity-mapping their metro area, moving from a sprawling urban agglomeration to an eco-tropolis. They defined major centers, small town centers and neighborhood centers that could over time attract more density, be connected via public transit, bike and greenways, and restore agricultural land, habitat corridors, urban streams and parks between and around them.

Tables 2 and 3 were jamming on the bio-geo-physical conditions for the city organism, finding the best ways to track and assess the urban metabolism of air, water, food, and material flows. Sebastian Moffatt presented his methodology of analyzing the material flows and forms through a Sankey diagram, an intuitive and accurate visual tool to measure exactly what goes in and what comes out of a complex system.

Table 4, facilitated by One Earth Initiative‘s Executive Director Vanessa Timmer, focused on the socio-cultural component of the ecocity — ecocitizens! No question, that was my kind of table, as I firmly believe that our physical environment is a reflection of our inner state and that lasting sustainable urban ecosystems go hand in hand with a creative, educated and conscious citizenry. I think we all agreed that the best indicator for the state of eco-citizenship is the strength of the community bond. While each community has their own particular culture and customs, common themes revolved around food, art, creativity, public spaces, education, easy access, and affordable housing.

It’s important to remember that socio-cultural conditions are very much interrelated with physical conditions. For example, it’s hard to engage with your community when there are no pedestrian areas and public spaces, but how do you get support for such infrastructure changes when everyone is used to driving their cars from their jobs to their garages? The answer is that you have to have temporary trials to show how much more fun and fulfilling life can be in closer contact with your neighbors. Convert one parking spot into a parklet and people will understand what it means to hang out in the street. Close down a street for a day and business owners will realize that it brings more people into their stores. In order to build growing eco-citizenship, changing physical spaces has to go hand in hand with changing mental spaces.

Table 5 was tasked with evaluating how the City of Vancouver — which has done an initial data search based on the 15 IEFS conditions — had fared in its assessment so far, addressing the gaps as well as new insights that could be shared with other cities in the region. While lacking in specifics, their presentation summed up the bigger picture quite nicely: “ All our Economy and Ecology are belong together!”

Friday, February 10th

The End(lessness) of Suburbia

The suburbs were set up as a kind of anti-community operation. Since the post-war period our economy has been geared to the task of building bigger houses farther apart from each other, and the biggest effect has been to erode community. If you’re in one of those big houses, isolated off on your own half acre, you’re not with other people. In the country you can be farther apart, but because life is a little rugged, you need other people and you seek them out. In the city people are used to bumping into each other, it’s just part of the attraction.

– Bill McKibben, The Biggest Fight of our Time

I woke up in the morning to a symphony of rain on my roof. My hostess had told me about a local umbrella shop a couple of nights earlier, so I thought that on my way to today’s workshop at BCIT’s Burnaby Campus this would be a great detour to check out something so unique to this bio-region that it wouldn’t have a fighting chance of surviving in the Bay Area. The workshop wasn’t scheduled until noon and from my metro map Burnaby looked like perhaps a 45 minute commute on the skytrain Expo Line, so after a quick coffee and muffin at one of the countless cafes in my neighborhood I started walking west on Broadway.

Broadway is not the most pleasant road to walk along, cars are clearly king and its long multi-lane-yet-still-congested blocks drag on and on.

When I finally reached the umbrella shop I realized it was on the other side, but I couldn’t cross the street because the only crosswalks on this auto-boulevard are at major intersections. I know that one of the main fighting chants by opponents of pedestrian zones is that car-access is vital for business. But how on earth can it be good for business if I can’t even cross the street to get to my store?

Anyway, the umbrella shop turns out to be great, a lot of their beautiful bigger models are made locally, and they run a whole repair service in the back. Repairing things seems like such an antiquated practice, and just the fact that I’m getting super excited about it is pretty scary and shows me how mundane the wasting of resources has become. The woman in the store tells me to check out the food market on Granville Island, the kind of tip you just don’t get on amazon.com. I make a note in my head to check it out after my afternoon session and walk off with my brand new umbrella that I hope will last me a lifetime.

I make my way downtown and hop on the Expo Line. There’s no direct connection to the Burnaby campus, but from the map it looks like it would be a fairly doable walk. After a 25 minute ride I get off at Patterson and start walking north. That is, I try to walk north, but I am once again confronted with having to cross a massive 8-lane road with blocks so long that the nearest crosswalk is several hundred yards in each direction. No way to jaywalk here, either. I used to be quite an accomplished Defender player in my day, but navigating through this onslaught of steel boxes would be instant Game Over.

I decide to go right and finally get to an intersection as big as several football fields, where I push the crosswalk button. I wait for what seems to be several minutes, and when I finally get a green light it turns flashing red the minute I step into the street. By the time I get back to the other side of the Metro Station to cut through a residential neighborhood that seems to be the shortest and least car-intensive route to campus I’ve probably already spent 15 minutes. I better pick up the pace now, our session starts in 20 minutes.

I walk down streets like this one…

with homes like this…

and endless side streets like this…

There’s not a soul to be seen anywhere, so it must mean I’ve arrived in the suburbs. I walk along a beautiful creek, the occasional fast-food wrappers lining my path.

This is taking me forever, and I still haven’t encountered a single person.

The sign says, “WOW, another dream come true!”

I finally get to the south end of campus, but that doesn’t mean I’ve arrived. I’m walking another mile to get to the main entrance, while everyone else is driving.

The theme of the session I’m trying to catch is to make the BCIT campus into an Ecocity School, a model that could be followed by others, and I immediately have some ideas. I’m imagining a student and faculty eco-village on this parking lot.

By the time I finally find “Town Hall D,” the room we’re meeting, I’ve missed almost the entire “Lunch and Learn” with Richard and Kirstin. But I do make it in time for Jennie Moore, Director of Sustainable Development and Environmental Stewardship at BCIT and IEFS Core Adviser, to report on the progress made since a campus ecocity design charrette was done a couple of years ago.

And they have been really busy! Jennie describes how the institute adopted a series of sustainability goals and how they went to work on the recommendations.

One of the things they did was hire two energy managers, Alexandre Hebert and Andrea Linsky. Alex gives us a rundown of the energy-saving projects they have taken on around BCIT’s campuses since he started in 2009. He describes how BCIT uses 44,000 gigajoules (GJ) of energy every year, and how they’ve already saved more than 9.5% of all electricity used annually, the equivalent of powering 440 houses for a year, just by installing auto-timers, high efficiency boilers, compressed air systems, efficient lights, and adopting “lights out” procedures.

They are now well on their way to reducing energy demand in the 7 main buildings by 75%. But this is just the beginning. Their commitment to sustainability encompasses not only green building design on campus, but employee stewardship programs, a greening curriculum & instructional practice, and community building programs in alignment with the goals of reducing their overall ecological footprint.

Speaking of alignment, much of what they have been doing is very much in line with the IEFS, and so the next part of the session is a deliberation by the various department heads on whether to become an official Ecocity School, spanning all branches of the Institute, from the School of Engineering to Health Sciences to Media and Creative Communications. Kirstin and Richard were facilitating the discussions.

It is really quite inspiring to see how far these determined folks have already come and how much farther they are planning to go in completely transforming 5 campuses with a population of over 15,000 full time staff and students, plus an additional 32,000 part-time students, into a zero waste, ecologically restored, greenhouse gas-neutral net energy producer. As Kirstin says, “they really walk the talk and we love them.”

And yes, I heard several people talking about replacing the ginormous parking lots with eco-housing. They’ve already adopted a policy that no more land can be used for additional parking and The Burnaby Campus Master Plan includes plans to “daylight” all of Guichon Creek from its underground culvert, from SE-16 at Ford Street all the way to Canada Way.

No doubt the Canada Way area could use some love. After sneaking out of the “town hall” I decide to make my way back via the Brentwood skytrain station, which is closer to campus but also means crossing both Canada Way…

and the Trans Canada Highway.

I wouldn’t call it beautiful, but there’s something majestically artful about these kinds of massive human constructs in their unbending will to subdue nature. And the difference in the perception of it depending on your perspective is so stark. If you’re sitting in a car — itself several thousand pounds of steel — you may pay attention to it or get a little annoyed by it whenever you have to slow down, but for the most part you don’t think much about it, because you’re just in it, a part of the painting, if you will. However, when you’re walking, it’s like you’ve been beamed to another planet. It’s like an assault on the senses, the noise, the pollution, the sea of concrete and masses of cars. The dimension, really, is not on a human scale.

There are so many cars in this world that they’re literally spilling over.

I think it’s a good exercise to walk on these kinds of stretches of land, just to stay tuned in and sensitized to what we’re capable of doing to the earth in order to get away from it. What should have been a 15 minute walk turned into a 45 minute meandering along these suburban arteries, at times just standing there watching everyone just going about their business behind their windshields. It may sound kind of sappy, but when you’re walking through a landscape like that, you can’t help but feeling sad, lonely and disconnected.

I have to say I was pretty happy to see the train after all that.

I did make it to Granville Island that day, but I will leave that for Part 3 of the journey.

That night, the dark and quiet of my little alley felt like a warm hand on my soul.

o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~

all photos by Sven Eberlein

Coming up in Part 3:

Granville Island

IEFS retreat

A tour of South Falls Creek Village

What a journey that second day was! It seemed like a boxing match between eco-change and ‘don’t mess with me and my stuff.’

The apartments I live in are set back from a 6-lane thoroughfare and sometimes I walk to the street so my daughter can pick me up quickly; I’m always frightened by the speed and power of the cars and the force of the air they send to everyone on the sides. And it’s the same here–crosswalks are few and far between. Two pedestrains have died near where I wait (trying to cross without a crosswalk) in the last two months. It’s NOT people-friendly.

Thanks for causing me to think about all this, Sven. You shed a whole new light.

Pam

Thanks for sharing, Pam. Isn’t it amazing how adaptable we humans are? I live on a big thoroughfare and most of the time I just kind of tune out all the traffic and noise. But then there are those moments when I just want to scream because it’s such a violent assault on my senses. I think those moments are moments of truth because they reveal just how big and overpowering the things we build are, and how alienated we become from each other when we’re all just sitting in big metal boxes blowing past each other on energy borrowed from a million years ago.

Thank you for keeping us “tuned in and sensitized.” Inside this fantastic insight, I found the photos of sessions meaningful in that they showed real people sitting at real tables. The enormity of the kind of change your tackling is astounding…unworldly…yet the ones who will make this happen are most definitely well-grounded Earthlings.

Thanks Ruth. Yes, I think that sometimes in all our frenzy to count carbon and come up with complicated schemes to “save” the world, we forget that ultimately this all has to happen among us human beings on the ground. Many of the problems we’re facing are because we’ve built things that are bigger than us, but I think that the solutions have to be on a human scale. That’s why I try to always include human interactions in my stories, no matter how small they seem to be compared to the largeness of an “issue.”

[…] Here’s what happened so far: Carless in Vancouver, Part 1: Boots on the Ground Carless in Vancouver, Part 2: Going for the high-hanging fruit […]