With the upcoming 21st UN Climate Summit in Paris (COP21) this December promising to be a multi-lane highway towards a low carbon society, it begs the question how this lofty aspiration squares with a 1.2 billion fleet of automobiles worldwide, projected to grow to 2 billion by 2035 and double to 2.5 billion in 2050.

While the number of cars and trucks in the United States has plateaued at a chunky 253 million (that’s 4000 pounds of steel, iron, rubber, plastics and aluminum for almost every man, woman, and child), global automobile sales are poised to soar to 127 million each year by 2035. If ownership in China catches up with the U.S. rate, there will be over a billion vehicles in that country alone.

Take a seat in the ecomobile for a moment to let those numbers sink in.

“Carden of Eden” at Flora Grubb Gardens, San Francisco.

No matter how hard I try, the math just doesn’t add up.

Consider: Science suggests that in order to stay within 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) of warming and have at least some kind of a stable climate, global greenhouse gas emissions will need to be at least 50 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. For that to happen, industrialized countries such as the U.S. would need to cut emissions more than 90 percent. Yet at the same time, the average fleet fuel efficiency needs to double just to keep carbon emissions levels of the projected 2.5-billion vehicle “global car parc” the same as today.

Seeing that cars are one of the largest net contributors to climate change pollution, it would seem that adding over 100 million of them each year is a bad recipe for greenhouse gas reductions. They would almost have to run on air for that equation to work, and that’s not even counting all the fossil fuels it takes just to make such heavy machinery available for our temporary enjoyment.

Perhaps this is a good time to re-envision the car of the future.

What about a BETTER car?

“But, but, but…,” I can already hear the protestations, “what about the great engineering miracle that is going to save the planet without having to take our foot off the gas electro pedal?”

I get it. It’s a seductive proposition, and on a personal level, if you must own an automobile, the case could be made in favor of an electric vehicle; though whether it has an actual net positive impact emissions-wise probably depends on where you live.

However, once you zoom out a bit to get more of a bird’s-eye view of the situation, you’ll find that the idea of a “better car,” while personally satisfying, does not stand the test of leading us to the kind of global greenhouse gas reductions needed to dodge irreversible climate feedback loops.

Feetless in Seattle

For one, only 2.5 percent of all new vehicles in the world are projected to run on battery electric, plug-in hybrid, or fuel-cells. That in itself is a good reason to discourage car ownership altogether, whenever possible.

But even if we could scale up the number of electric vehicles (assuming they could all be charged with clean energy) to, say, 50 percent, the emissions cuts required are so drastic that doubling the number of cars in the world between now and 2050 would automatically cancel any savings, no matter how energy-efficient these new vehicles are.

The same goes for “better” gas cars: It’ll be great to double the average fuel economy of new cars and trucks by 2025 (at least for some cars) and for car ownership to peak (or maybe not yet?) in the U.S., but it still leaves us with two people for every car in saturated western markets while the rest of the world is catching up at a breathtaking pace.

Remember, the science dictates that we need to get to at least 50 percent below 1990 levels of CO2 by 2050.

And that’s just the tailpipe of the melting iceberg

Another thing that very few people talk about is that the fuel powering your car is only, excuse the pun, the tail end of its carbon footprint. Manufacturing a new car creates as much carbon pollution as driving it, and with an energy and material life cycle as complex and obtuse as that of the automobile, that’s probably a very generous assessment. For example, coal, the most concentrated source of carbon dioxide on the planet, is an essential raw material in the production of steel, and it takes two thirds of a ton of coal just to produce a ton of steel. There’s a lot more under the hood than meets the eye.

Hooded bandshell in Fort Mason, SF

Then there’s the impact of building and maintaining the sprawling, car-dominated infrastructures that we in the developed world have become so accustomed to and people in China and India are poised to copy. Since these developments are often multi-sector and multi-jurisdiction projects, the true costs of sprawling, car-dependent infrastructure — from air pollution and carbon emissions to construction, noise, congestion, or injury from collisions hardly ever figure into any cost-benefit analysis.

However, a recent study on the hidden costs of suburban sprawl (pdf) points out the consequences of centering so much of our existence around the automobile: Canada, for example, spends far more on roads than it spends on transit and all other transportation system elements combined, with 69% of transport-sector emissions from road-based motor vehicles. It concludes that the more low-density the development, the greater the automobile dependency that results in higher energy consumption and GHG emissions.

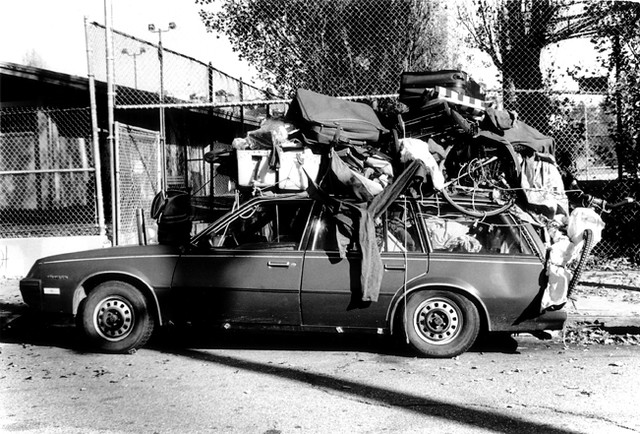

In other words, if your infrastructure forces residents to haul two tons of steel just to get a gallon of milk, it’s not sustainable.

View of Vancouver skyline from a Burnaby car lot

To highlight just how much more our car dependence is a result of structural necessity than of personal choice, look no further than the United States, where only 2 percent of federal transportation dollars are allocated for pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, with fossil-fuel interests now lobbying to cut all federal funding for walking, biking, and transit.

When people say they have no choice but to drive, it’s mostly because they’ve been given none. Really, who would want to be a pedestrian or cyclist in this manufactured landscape?

Somewhere in North America

The Auto Industrial Complex

It’s not just the physical effects. We are so enmeshed in the automobile as an unquestioned part of life that we’ve built a self-perpetuating culture around the industrialization of traffic, despite the fact that humans lived quite adequately without them for all but a tiny sliver of our history (only 100 years ago, cars were considered murder machines). The Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich expressed the deeper ramifications of our car-dominated existence in his 1978 essay, Energy and Equity:

The model American male devotes more than 1600 hours a year to his car. He sits in it while it goes and while it stands idling. He parks it and searches for it. He earns the money to put down on it and to meet the monthly installments. He works to pay for gasoline, tolls, insurance, taxes, and tickets. He spends four of his sixteen waking hours on the road or gathering his resources for it. And this figure does not take into account the time consumed by other activities dictated by transport: time spent in hospitals, traffic courts, and garages; time spent watching automobile commercials or attending consumer education meetings to improve the quality of the next buy. The model American puts in 1600 hours to get 7500 miles: less than five miles per hour.

While these numbers may have changed a bit over the years, the basic premise still applies: the car, for so many of us, occupies not only a significant physical but mental space in our lives, an object of our attention and affection, resembling in status and energy expended that of our home.

Perhaps even a spiritual home? With 2.5 billion car owners projected for 2050, there will be more automobile faithfuls than Catholics in the world.

President Eisenhower, in his 1961 farewell address, spoke of the dangers of the Military Industrial Complex, in which the very structure of society is built upon an economic, political, and even spiritual foundation whose continued expansion is not sustainable.

The same applies to the Auto Industrial Complex — just as it became clear at the end of the Cold War that there was a tipping point at which the benefits of weapons proliferation no longer outweighed the risks, we have come to a point in history where the economic gains of a growing global automobile fleet no longer supersede its social and environmental drawbacks.

In fact, with the existential dangers of rising levels of greenhouse gases so clearly understood these days that even the Pope warns about the grave implications of a model of development based on the intensive use of fossil fuels, there is now more than ever a moral imperative to deescalate the auto race and look for ways in which civilization can live, move, and thrive without being encased in armored resource guzzlers.

In short, we need much more than better cars. We need fewer cars!

Konviktstrasse in Freiburg/Germany: New urban design using medieval ideas of access by proximity.

Carsick Planet is a 3-part series excerpted from a photo feature originally published at Medium. All photos by the author, except where noted otherwise.

Coming up next:

Part 2: Shrinking the global fleet through personal, infrastructure & economic change

Fantastically illustrated!

I also love that you touched on the fear of NOT driving. You did this right after I viewed the “Feetless in Seatle” photo, one that made my heart retreat just thinking about walking through that landscape. What you’re suggesting here is that we mingle with each other, that our day-to-day living area shrinks, and that we see all the nooks, crannies, and nuances (the good AND the bad) of the cities, towns, or villages we inhabit. That’s a horrific proposition for some folks. Let me know what I can do to help you support it!

Hi Ruth, so glad you liked it. Just posted Part 2 earlier today. We humans are definitely creatures of habit, and all too often we cling on to the familiar even if it ultimately isn’t that great for us. Since cars are the status quo and so ubiquitous, most folks can’t even imagine what life would be like without them (or a lot fewer of them). But in my experience, whenever there’s a trial of a street closure for example all the people who screamed the loudest in protest before end up loving it the most. A common sentiment for example I’ve seen play out over and over in my city is that merchants think they’re going to lose all kinds of business during a car-free trial because customers won’t be able to drive right up to and park in front of their business. What happens in reality when the street opens up to pedestrians is that a lot more folks walk by their storefronts and they’re slow enough to peek inside. So all of a sudden they’re getting all this new foot traffic and they’re happy as clams. That’s why it’s important to have pilot projects, so you can tell people, “look check it out this one time, if it doesn’t work for you we won’t have to do it again.” Once people can see how the change affects them in real life, they overcome their fear of the unknown and of what they think will be an unmanageable and generally horrible situation. Thing is, we’re human, we’re made to walk! When we stop using our bodies they stop working for us.