In response to my recent post about composting food waste I was sent a graphic about e-waste, outlining another major component of our urban waste that is literally spiraling out of control. I usually don’t post these kinds of marketing gimmicks to drive traffic to other sites, but since this is a topic that needs a lot more attention, I’m okay with the “click-bait” aspect of it. I’m not familiar with the company that created the illustration, but at least it’s not Samsung or Apple. Then again, maybe gadget manufacturers would be the perfect purveyors of electronic waste statistics.

A few more thoughts about this graphic and its implications below.

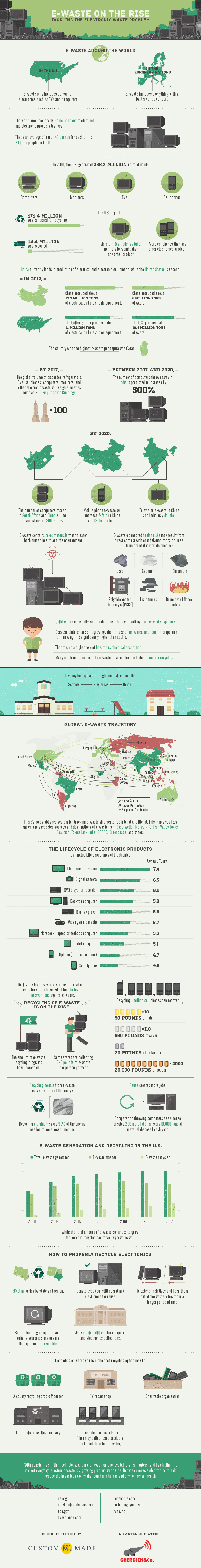

In a nutshell, electronic waste is out of control, and rising recycling rates are dwarfed by the rapid growth in production and consumption, with E-Waste projected to grow 33% by 2017 and the United States leading China as the world’s #1 producer of discarded electronics.What’s a bit fuzzy about the numbers is where it states that 171 out of 258 million of units of computers, monitors, TVs, and cellphones discarded in the US in 2010 were collected for recycling. Two thirds sounds like a pretty impressive (though still inadequate) rate, but the question is how many of these units actually get recycled, and if so, how, into what, and at what cost to whom, after they’ve been collected. According to Responsible Recycling vs Global Dumping, industry experts estimate that of the e-waste that recyclers collect, roughly 50-80 % of that ends up getting exported to developing nations.

This is where the trail gets very fuzzy and often leads to secret toxic waste dumps in remote villages from China to India to Africa, as illustrated by this Greenpeace chart.

Just the fact that they’re using this 50-80% window should tell us how little anyone really knows about the exact fate and whereabouts of our previous phones and TVs. Sure, there’s the Basel Convention, a treaty to control international shipments of hazardous wastes worked out by the United Nations Environmental Program in 1989, but it still needs to be ratified by the United States and 15 more countries due to the complexity over what constitutes a nonhazardous unit.

This is where the whole recycling business gets really tricky. Just like plastics, a lot of it is recyclable and manufacturers are very quick to put the three arrows on their products, but doesn’t mean it will get recycled or how much energy it will consume, how much pollution it will cause, or how it will affect workers’ health. In the case of electronics, it’s so much more complicated as there are so many different materials that need to be taken apart, including heavy metals like lead, cadmium and mercury.

It seems that no matter how much better we get at recycling these products in a safe manner, we will continue to fall short as long as the consumption levels keep increasing so drastically. To me, a big part of the problem is the proliferation of gadgets and the marketing that drives it. While it’s great that Apple for example is taking more responsibility and amping up its return and recycling efforts, the problem is that they also make it so seductive and necessary to buy a new phone every other year, or even more often.

What if Apple made products that last longer and encouraged to hang on to our old ones for longer, the way Patagonia does for its jackets?

I feel like the pushers of new technology always tempt us with promises that their latest inventions are going to be more environmentally friendly. Remember how computers were supposed to save paper? Or reduce energy consumption?

In the end, all the increased efficiencies that technology promises and often even delivers are almost always offset by a flawed economic system based on consumerism and perpetual growth that has laid more waste to the planet’s natural system over the past 60 years with each advertised brilliant technological invention.

Or as Annie Leonard puts it, a system set up to externalize true costs and design for the dump…

As I am sitting here typing these words into my computer I understand the inherent difficulty in finding easy solutions to this problem. I think it has to be a combination of things, and not just of a physical nature. Yes, there has got to be a comprehensive international system of ensuring that these mountains of e-waste are being reused and recycled responsibly and equitably. But there also needs to be more accountability on the manufacturers’ end for the type of products they’re introducing to the market.

While these kinds of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies have gained ground in Canada and the EU in recent years, there is no federal law governing EPR or product stewardship in the United States, though individual states like California have made strides in some areas of manufacturing.

Beyond that, we have to change our thinking, both from a producer and consumer point of view. Companies who talk the green talk need to walk the green walk and take responsibility for the entire life cycle of their product, with or without regulation. Becoming registered Benefit Corporations will enable them to eschew the profit-above-all-else modus operandi their traditional corporate bylaws dictate, forcing them to do the wrong thing for people and planet. It’s possible, just ask Patagonia.

On the other side of the equation, we as conscious humans who understand how overstretched this planet is and how our own choices set the tone for how we tread on it have to learn how to say no and go slow. We need to resist the temptation to acquire the latest shiny object, stretch the lifetime of our possessions, find opportunities for creative reuse, and support the companies that are committed to manufacturing the cleanest, most energy-efficient, repairable, and highest quality products.

Above all, we need to help each other rediscover the part of ourselves that values experience, friendship, passion, creativity, and all the other non-material treasures of life we won’t be able to take to our graves.

I’m so glad you followed up the recycling numbers with valuable information about where those recyclables are truly going as well as companies that are working toward a solution.

(I understand e-Stewards is resource for finding responsible recyclers: http://e-stewards.org/about-us/the-e-stewards-story/)

Meanwhile, I’m also glad you pinpointed the fundamental problem and the easiest part for us to control: limiting consumer purchases. It can be done. I am still using my second cell phone. My first one was bought in 2006, after pay phones began disappearing. I think I bought the second one in 2007, because I couldn’t hear conversations well on the first. I’m am writing to you using my second desktop computer, an Apple Mac Mini purchased in 2009. My husband just gave up on a MacBook laptop that was even older than that, but I’m holding on to it ’cause it still works for typing notes at meetings, etc. I don’t know how old the monitor is; I acquired it from a friend who no longer needed it. We upgraded our television when the old one died. Same with everything else that plugs in around here. Buying decisions were investments for the long-term, based on needs, with the intent to not buy again until absolutely necessary.

My phone is dumb — it only makes and receives phone calls. My computer is slow by today’s standards. Every once in a while I find myself in situations where I must reach out for help because I don’t have a technological appendage, such as asking for directions or inquiring about a good place to eat. But in the day-to-day, my tools work.

Normally, I’d have no outlet to brag about the age of the electronics I own (or lack thereof). Once upon a time, you could be proud when you maximized the life of your possessions. Now I cower in the corner to flip open my phone and make a call.

Ruth, I’m in the same boat as you. I take pride in stretching the lifetime of any device or appliance I own as far as possible. Personally, I’m less concerned with the outdated look of a gadget (I love my dumb phone, it does exactly what I want it to do and keeps me off the internet when I leave my house 🙂 ) than about its functionality. The great thing about a flip phone is that it doesn’t really lose its basic function of making calls or sending texts. So it’s possible to keep the same one until it physically breaks if you choose to do so. But it’s a different story with computers, tablets, and smartphones, as they are designed to lose their functionality long before they reach the end of their physical life cycle, because of constantly updating software, memory, and security features. And that’s what’s really kind of scary — that by moving to the latest iterations of technology we’re implicitly giving up our own CHOICE to hang on to cherished products, no matter how well we care for them.

Not to be too sentimental about older technologies, but there’s something to be said for being able to turn a 50 year old possession into a fully functioning art project. Who is going to care this much about an iPad in 50 years?

Thank for, Sven, for the excellent expose on the truth about e-waste. Much of it ends up in the so-called developing countries where children and women living in slums pick apart and burn the circuit boards to extract what is valuable but exposing themselves to toxic fumes in the process. I am surprised to see in the Greenpeace info-graphic that Delhi is a destination for such e-waste from the US and EU. It’s the fricking capital of India! I am not sure industry has figured out a way to extract the recyclable components in a more humane manner. It’s not worth the expense. They’d rather hide it away from those who might complain.

The emphasis at major tech companies in Silicon Valley is to remove all e-waste out of sight of their employees as quickly as possible. They contract with companies that specialize in this. Big trucks are brought in regularly to haul away all the e-waste. Maintaining a culture that doesn’t show the tail end of a destructive process is highly important to these companies. Employees are even encouraged to bring in e-waste from their homes to dump into special receptacles that are emptied often. Used batteries and even paper-to-be-shredded is accepted. All this keeps the techie tapping away at the keyboard all day oblivious of the life-cycle of the products and gadgets they are encouraged to design and build for the world to use.

Thanks for chiming in, Satish. In many ways, these companies’ efforts to recycle their gadgets — however genuine — are actually counterproductive, as they reinforce the myth that computers and gadgets will somehow magically end up being shiny new gadgets again. It’s no different from the plastics industry and their promotion of “recyclable” plastics that I mention in my post. Just because it’s “recyclable” doesn’t mean it WILL get recycled. In some ways, almost any material thing is “recyclable” but it ends up getting conflated with having “no impact,” whether that’s intentional marketing or just wishful thinking. Probably a combination of both.

Recycling is often a very dirty, energy-using process, and like you say, the impact of trying to recycle old electrics on the workers and communities at the end of the line is horrific, but mostly ignored or externalized by the manufacturers as well as consumers. What we really need is some brutal honesty and intense reflection of our entire industrialized system, the way you have done, on a large scale, for we will never be able to heal if we don’t look at what’s causing the disease.