Nuclear Poker Heats Up in Berlin is the title of an article in this week’s edition of Der Spiegel, the widely respected German news magazine. Elections have consequences, they say, and with Angela Merkel’s center-right Christian Democrats (CDU) poised to say good-bye to the grand coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD) and tie the governing knot with the libertarian-leaning Free Democrats (FDP), some of that feelgood eco affection the American left has had for Germany may have to cool off for a while. Case in point: Talk of a possible hold on the nuclear phase out by 2020, legislated in 2002 under the distant memory of a Social Democratic/Green coalition.

Here are some reflections on a touchy subject from a native German who grew up during the “nukin’ 80s” that I think are also relevant in light of President Obama earning the Nobel Peace Prize, attaching “special importance to Obama’s vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.”

Just to be clear, they’re not (yet) talking about reversing the decision to quit nuclear power, just about extending the deadline, “a move that could generate as much as €60 billion in extra profits for Germany’s three largest energy companies.” But while about 60% of Germans are still in favor of the phase-out, the fact that stocks for these three nuclear power utilities climbed 5% the day after the election on speculation that Chancellor Angela Merkel’s favored coalition government will scrap the law should be reason for concern.

To say that you still want to phase out nuclear power, just not at the previously agreed upon date, is a delicate, and some may say, ominous, political dance. It is with one hand playing to the 60% majority opposed to nuclear power, and with the other buying time to whittle away memories of past accidents and allowing a powerful nuclear lobby to put their big foot in the door left intentionally open. In other words, if you thought Gerhard Schroeder and Joschka Fischer had forever put the nuclear genie back into its bottle back in 2002, think again: Chancellor Merkel and her new cabinet are about to pop that cork again.

I understand that people feel very strongly on both sides of this issue. Proponents of nuclear energy often cite France as an example of nuclear success: With almost 80% of its energy coming from nuclear power, they point to its safe, clean, and peaceful use. They argue that nuclear power as an important carbon-free source of power could play an important role in reducing worldwide greenhouse gas emissions while maintaining our current standard of living. A lot of them are thoughtful people who also advocate the increased alternative sources of energy like wind and solar.

But I’m sorry guys, I can’t go there with you. As a German who came of age during the height of Cruise Missiles, Pershing 22s, and Chernobyl, I feel it my duty to serve as the firewall between ostensibly low-hanging energy fruits and rejuvenated technological overconfidence. You can throw all kinds of numbers at me that prove how safe and advanced nuclear technology has become, and that’s fine, I believe you. They also say flying is the safest way to travel, and they’re right. But you know what, shit still happens, planes crash, computers fail, humans err. That’s okay with me, I’ll take my chances getting on a plane, but I’m not willing to take that chance with the nuclear plant, no matter how small the odds of a meltdown.

I admit that coming of age in the throes of a cold war in which your country serves as ground zero for two global superpowers armed to the teeth with nukes to work out their unresolved issues will leave you a bit jaded. And when Reactor#4 at the nuclear plant in Chernobyl melted down in 1986, my fate as a permanent Green Party supporter was sealed. I don’t know about you, but something is wrong in my opinion when 18 year-olds in fear of getting doused in radioactive rain sit at home talking about the annihilation of the human race. But that was exactly what my friends and I “were into” during those days.

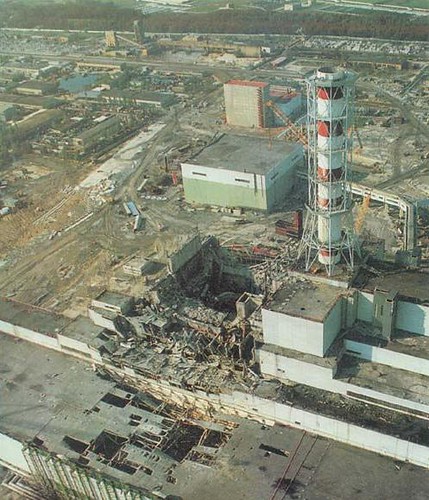

Chernobyl disaster

26 April 1986 (1986-04-26)

01:23 a.m. (UTC+3)

Pripyat, Ukraine

The nuclear reactor after the disaster. Reactor 4 (centre). Turbine building (lower left). Reactor 3 (centre right). 600,000 (est) suffered radiation exposure, which may result in as many as 4,000 cancer deaths over the lifetime of those exposed, in addition to the approximately 100,000 fatal cancers to be expected due to all other causes in this population.

Source: Wikipedia

And while the Social Democrats offered no more than a lukewarm opposition to Chancellor Kohl’s staunch pro-nuclear policy, it was the Green Party that coined the term “Atomkraft? Nein, danke” (Nuclear Power? No, thank you) around the same time Nancy Reagan said no to drugs an ocean away. Hiroshima, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl — despite our undoubted technological prowess I did not believe that we humans should continue to experiment with the fragile nature of atoms; annihilation of life on earth seemed too large a potential side effect. That’s why we spent our Saturdays camping out at the Neckarwestheim nuclear plant demanding to have it shut down instead of going to the disco.

And while the Social Democrats offered no more than a lukewarm opposition to Chancellor Kohl’s staunch pro-nuclear policy, it was the Green Party that coined the term “Atomkraft? Nein, danke” (Nuclear Power? No, thank you) around the same time Nancy Reagan said no to drugs an ocean away. Hiroshima, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl — despite our undoubted technological prowess I did not believe that we humans should continue to experiment with the fragile nature of atoms; annihilation of life on earth seemed too large a potential side effect. That’s why we spent our Saturdays camping out at the Neckarwestheim nuclear plant demanding to have it shut down instead of going to the disco.

Atomkraftwerk Neckarwestheim

Personal memory alone of course does not make sound public policy, but it serves as a foundation to inform and shape public policy. Just as past wars and all their personal suffering have led to peace treaties, and past prejudice with its heart-wrenching stories of injustice have led to anti-discrimination laws, it was those deeply terrifying collective experiences my generation of Germans had with nukes in the 80s that led to the phase-out decision in 2002. The election of a more nuclear-friendly government may be a tribute to the comforts of two decades without malfunctions, but nuclear memory is as long as the half-life of an atom.

While these issues of safety, in my opinion, should be concern enough to be dealbreakers in the maybe-it’s-not-such-a-bad-idea-after-all discussion, there are other compelling reasons why the new coalition would be ill-advised to tamper with the phase-out. Nuclear waste and our inability to dispose of spent fuel rods that remain toxic for thousands of years is one of them. Falling into the wrong hands is another. The staggering cost of nuclear power is another. The list goes on.

However, the biggest reason why it is so important for Germany to keep its commitment to phase out nuclear power is because of the example it would set. If one of the richest, most educated and tech-savvy countries on earth cannot make the shift to a post-carbon fueled world without playing the risky and dangerous nuclear roulette, then what message does that send to less wealthy, politically stable, and technologically advanced countries? If a rich western country that has staked its claim as a leader in reversing climate change signals that nuclear power is a viable alternative alongside wind and solar, then how do we keep less alternative energy developed countries from going nuclear? And finally, what kind of example does it set when the pioneers in energy conservation and smart urban planning continue to go nuclear?

Although Global Warming has only recently entered the mainstream discourse, it’s not like these energy issues are new. Jimmy Carter talked about it in 1977. I and many of my fellow Germans were pondering whether there could be better, cleaner and safer ways of harvesting energy, and if, God forbid, we could just collectively scale back a bit in our luxurious Western lifestyles, all through the 70s, 80s, and 90s. You know, solar and wind energy, walk and bike more, redesign our cities, spend more time reflecting and breathing, take a chill pill! Anything but more nukes.

Again, word is that this might only be a temporary extension of the phase out, and that up to €50 billion of the profit windfall generated could be mandated for the promotion of renewable energies. But I see a sign that reads:

Caution! This pandora’s box makes sudden turns and may be harmful to your health.