If indeed the continued proliferation of the personal automobile is not compatible with the future we want as I have suggested in Part 1 of this series, the question naturally becomes: How exactly are we going to “disarm”?

Let’s first posit that the goal isn’t to reach “zero cars,” as such a drastic all-or-nothing approach is neither feasible nor necessary. There will always be a need for useful and necessary motorized transportation, from delivery, emergency, agricultural, and transit vehicles to serving residents in remote areas or people with limited physical mobility. As noted in the previous post, there are also existing suburban developments that will force its residents into car-dependence in the near term. (Whether these kinds of sprawl patterns are sustainable at all is another question).

However, with almost 70% of the world’s population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, there is a large pool of car owners living close enough to basic services that could be enticed to live car-free, given the right circumstances.

What might an attainable reduction look like? Matching the IPCC’s latest World Carbon Budget recommendation of 50% reduction of 2020 peak emissions by 2040, a corresponding goal could be for a 2020 fleet of roughly 1.5 billion to be cut in half by 2040, to 750 million. Figuring in the improved fuel efficiency of newer fleets, let’s even allow for an additional 250 million vehicles, setting the minimum target at 1 billion cars globally in 2040, one for every seven people on the planet.

Reducing the number of cars from the current 1.2 billion to 1 billion, an 18% reduction within the next 25 years, seems like a reasonable, albeit ambitious target.

Just as with international climate negotiations, the targets for reductions would be much steeper for developed nations. While developing countries would have to drastically curb their growth rate in automobile ownership, most European and North American countries would have to set much higher reduction targets than the 18% needed globally. Getting from one out of every two people driving to one in seven will require a structural and cultural paradigm shift on par with WWII mobilization in the United States or the Marshal Plan in post-war Germany, beyond even the most rosy current projections for some European cities to reduce the share of journeys by car from 50% in 1990 to 27% by mid-century.

Is a world in which people outnumber cars 7:1 really so hard to imagine? I don’t think so…

Getting to 1 Billion Cars (1 for every 7 people on Earth)

Let’s be frank: Forcing people to give up their car or not buy a new one would be about as effective as the “War on Drugs.” Once people are hooked on something, prohibition rarely works and, in fact, usually generates the opposite of the desired result, even if it’s deleterious both personally and to society at large.

Thus, a large-scale shift toward alternative means of transportation has to be voluntary, driven by a change in values. A change in values usually occurs when something different is viewed as being more practical, economic, and enjoyable, and a big part of making car-free living more practical, economic, and enjoyable is to create the physical conditions to allow and encourage this kind of lifestyle preference.

There are, however, economic forces that can regulate the price and consumption of a product, so let’s be frank again: The price we are currently paying for the convenience of a personal automobile does not reflect its true cost. If we were to take into account all the environmental, social, and health costs incurred by car ownership, the price tag per vehicle would be much higher, thus reducing demand.

The keys, therefore, to shrinking the global car parc for the first time since the invention of the automobile are threefold:

- Growing desirability of car-free living

- Transformed infrastructure enabling widespread access by proximity

- Paying the true cost of automobility

1. Growing desirability of car-free living

Making voluntary cutbacks is usually a tough proposition, as the human mind seems to generally be tuned to seek something more and better. However, therein also lies the greatest opportunity for change. As the volume of cars in the streets is reaching a tipping point at which the promise of mobility is often overshadowed by congestion, lack of parking, noise, pollution, accidents, and the prospect of climate chaos, the opportunity arises to promote a car-limited lifestyle and environment as something more and better.

For example, instead of a time-consuming, solitary, and sedentary commute…

wouldn’t it be so much better to have a quick, communal, and healthy one?

Instead of dangerous, congested, polluted and noisy streets…

wouldn’t it be better to have streets we didn’t need to admonish our children to stay out of?

Instead of having to use most of our public land as car storage…

wouldn’t it be so much more healthy and inspiring to reclaim them as people spaces?

Instead of constantly searching for parking…

wouldn’t it be so much more relaxed to enjoy a picnic in the park(let)?

You get the idea. The good news is that there is not much convincing to do. Recent research shows that the psychological benefits of an active commute are so significant that most people place them on par with a happy marriage or a pay raise. Better yet, four in five millennials say they want to live in places where they have a variety of options to get to jobs, school or daily needs, and three in four say it is likely they will live in a place where they do not need a car to get around.

Walkscore, the service founded in 2007 with the mission of helping people find a walkable place to live, now shows more than 20 million Walk Score, Transit Score and Bike Score ratings every day to home and apartment shoppers across a network of more than 30,000 websites and apps. In fact, demand for car-free living has been so overwhelming that in the United States the cities with the highest Walk Scores like New York, San Francisco, and Boston have become so popular they are now facing unprecedented housing crises.

Which brings us to Key #2:

2. Transformed infrastructure enabling widespread access by proximity

When looking at our current automobile-centric infrastructure it’s tempting to assume everything naturally evolved that way. Really, with most waking moments of our lives so intrinsically tied to motor vehicles, it is hard to imagine there ever having been a time when our physical and mental spaces weren’t revolving around acquiring, operating, accommodating, maintaining, storing, routing, parking, and dodging this ubiquitous yet humongous part of our lives.

The car has become so second nature to most of us that I often find myself the only person awed enough to take photos of these types of stunning urban scenes that play out in cities across the world while everyone else goes about the business of navigating through or around the metal labyrinth as if it were their living room furniture:

Another day trying to cross the street

The truth is not only that our communities didn’t always look like this, but that the tremendous changes our streets have undergone over the past century happened neither naturally nor by chance. Up until about 100 years ago, city streets were populated by pedestrians, pushcart vendors, horse-drawn vehicles, streetcars, and children at play. Back then, if you wanted to cross the street or toss a baseball you could just do it without fear of bodily injury or being fined 250 dollars.

When the number of cars in the United States suddenly spiked during the 1920s, a slew of pedestrians lost their lives by simply doing what they had always done — moving about in the streets, the way they still do today in many countries across the world.

Whose street is it anyway?

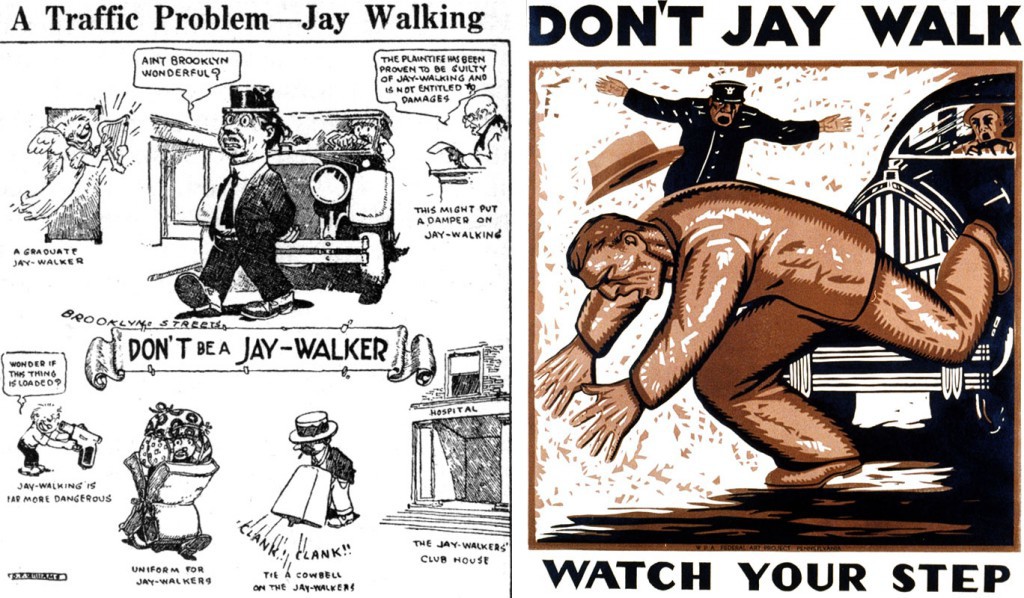

Rulings in court cases usually assigned fault in those collisions to the larger vehicle, charging drivers with manslaughter, regardless of the circumstances of the accident. As University of Virginia historian Peter Norton chronicles in his works Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City and Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street, public outcry at these violent intruders that were viewed as rich people’s joy rides led to a huge backlash, including the erection of monuments for children killed in traffic accidents, editorial cartoons depicting drivers as grim reapers, and ballot initiatives calling for governors capping cars at speeds of 25 miles per hour.

Automotive interest groups recognized both the legal and psychological barriers they were up against and launched organized campaigns to redefine streets in favor of cars. With the help of then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, the Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance was passed in 1928, a federal law still in effect today that restricted pedestrians to narrow angular sections of the street (aka crosswalks) and shifted blame in collisions to non-motorized citizens. To this day, drivers who kill pedestrians rarely face punishment.

Crosswalk infringement

Along with the official enshrinement of car supremacy, nothing was as instrumental in bringing about “the end of walking” as a nationwide shaming campaign that mainstreamed a previously unknown moniker for those who didn’t get the memo about the new rules of the road — jaywalking.

1923 editorial cartoon mocking jaywalking and WPA poster pointing out the dangers of jaywalking. National Safety Council/Library of Congress

Once the tipping point had been reached at which it was considered more normal to drive a car than to walk in the street, all civic gears kept on churning toward maintaining and institutionalizing the new car-first paradigm, with a mandate to make driving as comfortable, efficient, and safe as possible while making pedestrians bystanders in a street hierarchy ruled by cars. With all roadblocks literally and figuratively removed, the way was paved (pun!) for the commodification of the personal automobile and the infrastructure required to operate them at will.

Today, evidence of this surrender to the navigational needs of 120 cubic foot motorized carriages is all around us, from minimum parking requirements to forced separation of commercial and residential zones and from ubiquitous gasoline subsidies to gross funding inequities between highways and pedestrian passages.

In the United States, perhaps one of the most ingrained purveyors of structural car privilege is a little known, benign-sounding transportation planning rule used by traffic engineers, called Level of Service (LOS). LOS dictates that any time a change is made to an intersection, the effect that change will have on car traffic must first be calculated. Therefore, if a municipality wants to widen a sidewalk or add a bike or public transit lane to an existing road, it can only do so if it doesn’t slow down the flow of car traffic.

In other words, tinkering around the edges — yes; building a foundation for a walkable, bikeable and public transit-oriented urban ecosystem — no.

Stuck between a parked car and a hard place

The good news — and the reason it’s essential to be aware of the history of how we got to where we are — is that just as existing infrastructure is the result of concerted efforts from all segments of industry, government, and society, these transportation patterns can once again be transformed if we collectively decide it would be beneficial for all stakeholders involved. Looking at the greenhouse gas emissions numbers as laid out above I think it’s fair to say that there aren’t many stakeholders who wouldn’t benefit from signing on to a new vision of how we get around (safe for a few short-term profit-driven fossil fuel interests).

Simply put, we need to make it easier for people to get to where they need to go without driving. A good place to start is to enable those who already live close to their daily destinations to get there safely and comfortably without a car. In the United States, for example, 65 percent of trips under one mile are made by automobile, mostly due to dangerous streets that make it unpleasant to walk, bicycle, or take transit. With 28 percent of all trips taken being a mile or shorter, focusing on relatively minor street improvements like widening sidewalks, designating separated (and pothole-free) bike lanes, and adding bus service can yield huge returns in car trip reductions for relatively small investments.

sidewalk widening and bike path construction

For that to happen, archaic rules like “Level of Service” need to be updated to figure in the benefits of increased pedestrian and bicycle traffic to intersections. This type of essential change on a policy level is already beginning to take hold. The State of California recently became the first state in the US to ditch LOS altogether: instead of measuring whether a project makes it less convenient to drive, the substituted Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) guideline will “measure whether or not a project contributes to other state goals, like reducing greenhouse gas emissions, developing multimodal transportation, preserving open spaces, and promoting diverse land uses and infill development.”

separated bike path = safe bike travel = more cyclists = cleaner air

Another important and attainable policy change to foster less car-dependent infrastructure in the United States is the conversion of outdated zoning designations that create too much distance between residential and commercial areas to mixed use zones, allowing for people to live, work, play and shop within a the same area. Cities like Baltimore, Tulsa and Washington D.C., whose current zoning ordinance dates back to 1958, show that there is movement in the right direction. Housing developments like the “Garden Village” near downtown Berkeley in which a small fleet of four to 10 automobiles operated through a “car-share pod” will service 77 units reflect the people-centered zoning of the future.

Of course, when automobility is so deeply ingrained in every fiber of your infrastructure, it takes a long time for a zoning change here and a bike lane there to reach enough of a critical mass to fundamentally change our Modus Operandi. Swimming against such a forceful tide can not only lead to frustration on part of the change agents but embolden car enthusiasts to dismiss the advances as piecemeal or non-functional. Therefore, it is important to remind ourselves that almost all of the cities that have become showcases for their forward-thinking urban design policies were at one point facing the same challenges and skepticism as today’s adopters of pedestrian- and transit-first principles.

For example, in Freiburg, Germany, the planning director was widely ridiculed and eventually run out of town for modeling the city’s post-war reconstruction after the original medieval blueprint. Today, the European City of the Year in 2010 is celebrated for its beautiful people-centered downtown.

Or take Amsterdam, the flagship of pedestrian- and bike-friendliness that wasn’t always so. The Dutch city became overrun with cars after World War II, but the oil crisis in the 1970s led to the demand by a vocal group of activists for large-scale, structural changes. It took decades of resistance by people fighting for the the status quo, yet the ideas prevailed and today pedestrians and cyclists are the status quo in all of Holland.

Vancouver B.C. has been working on greening itself for over 40 years, creating better density and accessibility North American-style.

And in Medellín, Colombia, a city that had to overcome a complete collapse of its civic institutions during a brutal drug war was able to transform itself from most dangerous city in the world in the 1980s to current U.N. poster child for urban equity. Through its bold social urbanism reforms, the city built its visionary new public transit system not only to relieve congested roads, but to reintegrate marginalized communities into its social and economic fabric.

Clearly, a shift in urban policy and planning by local municipalities toward easier local access driven by a change in values as to how we want to live and get around goes a long way in laying the foundation for a world with fewer cars. However, the proliferation of the personal automobile will continue unencumbered unless a crucial third — and most systemically ingrained — challenge is addressed in earnest.

3. Paying the true cost of automobility

Externalizing costs is by no means limited to the automobile industry. In fact, the omission of any kind of accounting beyond the most visible, short-term, and personally applicable expense is the engine that has driven most modern industrial advances through the profit-first mechanisms enshrined in the capitalistic system. Almost all the current wealth in this globalized system, whether it’s personal, corporate, or national (GDP), has been the result of exploiting finite natural resources for short-term gain without accounting for the steep social and environmental costs to the greater commons and future generations associated with the degradation of the Earth’s ecosystem. As Pope Francis points out, capitalism’s assumption of infinite or unlimited growth “is based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth’s goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry at every limit.”

So when Europeans buy an apple grown in New Zealand at their local supermarket, the fifty cents they pay does not account for the cost of carbon emissions from an 11,000 mile transport, and the grower’s, distributor’s and transporter’s expense sheets do not include the cost of damage from oil extraction to local communities in Ecuador or Nigeria. When Americans buy a new television set made in China, the three hundred dollars they exchange with Best Buy or Amazon will cover neither the product’s carbon footprint nor the plastic pollution from its packaging nor the environmental and health costs of toxic e-waste at the end of the television’s (intentionally short) life cycle to disposal sites in Ghana and Bangladesh.

The same goes for the cost of a car, although starting at $20,000 a unit it does not appear artificially cheap at first glance. The fact that the automobile is one of the most expensive acquisitions in most people’s households makes the industry immune to the kinds of critical exposés that we’ve come to expect about the food or electronics industries. While the breathtakingly low price tags for certain types of produce or consumer electronics may give even the most ardent discount shopper pause at times, it is much more of an intellectual exercise to feel this kind of reverse sticker shock from the acquisition of a car. “Twenty-five thousand dollars for this truck is such a steal” said nobody ever.

In a way, the costs of the car as a common household item to people and planet are so manifold that the mere thought of them can be overwhelming. The immediate human toll alone is so staggering that people would think twice before starting their car if they weren’t in denial about these realities:

30,000 people lose their lives on American and Russian roads every year, over 200,000 in China, and 1.24 million worldwide, projected to increase to 1.9 million people annually by 2020. One person is killed by a car every 25 seconds, half of them the most vulnerable road users like motorcyclists, pedestrians, and cyclists. That’s not counting millions upon millions of (often unaccounted) injuries, combining for a mind-boggling $518 billion total annual cost of road traffic crashes, according to the World Health Organization.

In addition to these tremendous primary health costs of automobile proliferation, there are countless secondary ones. The American Lung Association reports that in California alone, a state that boasts one of the most stringent auto emission standards in the world, its fleet of 30 million consumes 12.2 billion gallons of gasoline per year, leading to an output of 18 tons of fine particulates and 272 tons of smog every day. Counting 11,400 asthma attacks, 550 heart attacks, 610 cardiac/respiratory ER visits and hospitalizations, 715 cases of chronic and acute bronchitis, and over 50,000 lost work and school days, cars are causing $14.5 billion in health and other societal damages each year, nearly $20 in damages with each full tank.

This, of course, only accounts for tailpipe emissions. There are numerous car-related environmental, social, and health costs that — while harder to tally in exact dollar amounts — contribute to the severe undervaluation of each vehicle. There is the above-mentioned environmental cost of one car, cradle to grave. There’s the irreparable degradation of delicate ecosystem all over the world from rock and gravel extraction in large quarries and road construction itself. Not to forget the costs to public health incurred by a sedentary driving lifestyle that contributes to high rates of diabetes and obesity.

Arguably one of the most ignored yet consequential costs of automobility is the wholesale destruction of minority and disadvantaged communities through big car-centric development. In the United States, for example, the 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act wiped out Mexican barrios, Chinatowns and black commercial districts such as the Village Bottoms in West Oakland, where the construction of the Cypress Freeway effectively severed the existing tight-knit African American community from the city’s more affluent communities and its services. Today’s urban food deserts, whose high rates of unemployment, poverty, crime, and pollution have taken a severe toll on residents’ health and welfare, are often the direct result of discriminatory policies and patterns of development in the name of automobility.

Construction of the Nimitz Freeway severing West Oakland. Photo: Oakland Tribune Collection.

Then there’s the true cost of oil. Artificially cheapened by subsidies estimated to be $1.9 trillion worldwide each year, the money we pay to fill our gas tanks doesn’t even begin to cover the enormous long-term risks, impacts, and costs to people and planet.

Aside from the moral implications of burning the lion’s share of a finite resource that took millions of years to form for the temporary convenience of just a few generations of humans, the price of a gallon of gasoline at the pump epitomizes the externalization of a product’s actual cost: from the destruction of ecosystems to extract it to the wars fought to secure it and from the dangers of transporting it to the pollution from combusting it, there is probably no other commodity besides petroleum with as long of a list of expenses conveniently erased from our collective balance sheet. Recent drops in prices at the pump that are driving up gasoline use in the United States despite more fuel-efficient fleets demonstrate just how absurd and destructive the externalities-based economy really is.

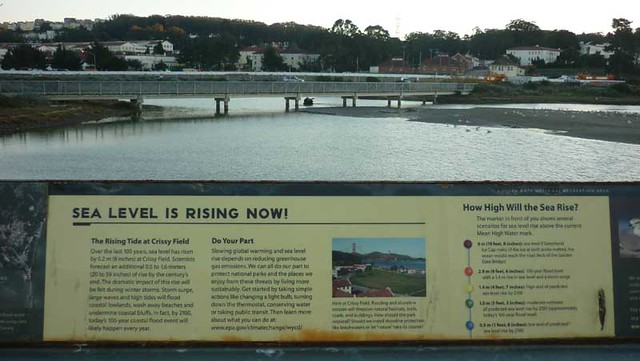

This is all before we even get to the elephant in the road, the cost of global atmospheric warming. One of the world’s largest net contributors of greenhouse gases (GHG), each gallon of gasoline burned by a typical car creates 20 pounds of GHGs, about 7 to 10 tons each year. In the U.S. alone, vehicles release 1.7 billion tons of GHGs into the atmosphere each year just from tailpipe emissions, estimated to contribute to an economic loss of $180 billion by the end of the century if we don’t curb global greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, adaptation costs for the world’s least developed countries, many of which are among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, could jump as high as $1 trillion a year by 2050.

For anyone without extreme blinders around their immediate personal economic comfort zone these facts and figures lay bare the discrepancy between the retail value of a car or a gallon of gasoline and the actual cost these everyday items incur on ecosystems, humanity, and the future of life on Earth. To put it in economic terms, our entire global automobile infrastructure and the way of life based around it is like an enormous credit card, and the money we spend on purchase price, sales, vehicle and gasoline taxes barely covers the interest on the degradation of the natural life systems we depend on for survival, caused by this massive intrusion.

As such, a more holistic accounting of the complete costs associated with operating an automobile must be at the heart of infrastructure policy as well as consumer choices, lest we default on our ecological debt.

The good news is that this needed shift in economic vision from externalized and exploitative to thorough and sustainable is already surfacing, both through proactive endeavors as well as markets responding to the implausibility of perpetual growth-based projections on finite resources.

On the proactive end, cities, universities, foundations, and faith-based organizations across the globe are making commitments to divest from fossil fuels. Corporations like the Guardian Media Group are making hard-nosed business decisions based on ethical and financial grounds to pull out of all their coal, oil and gas holdings to the tune of £800 million ($1.25 billion). In the largest divestment move from coal in history, Norway’s parliament recently endorsed the sell off of $900 billion in coal investments from its sovereign wealth fund.

On the responsive end, from California to Quebec and from Finland to China, states and countries the world over are beginning to put a price on carbon. Even the most flagrant externalizers in the world — dozens of the world’s largest corporations, including the five major oil companies — are preparing to pay a price for their carbon pollution. With a binding global climate treaty likely to be signed at the upcoming Paris Climate Change Conference, — two-thirds of already accounted for fossil fuel reserves will have to remain in the ground if the world is to avoid the threshold for “dangerous” climate change — extractors have no choice but to react to this carbon bubble, recognizing that their stock value is hyper-inflated.

Without question, the promulgation of the automobile as a consumer item in every household has been driven by an economic system using the artifice of cheap oil not only as its engine but its raison d’être. Consequently, any good-faith attempts to transform infrastructure patterns toward prioritizing pedestrian and bicycle mobility or to sway people’s personal choices toward car-free living can only be successful on a systemic scale once the underlying economic dynamics cease to force decision makers as well as their constituents into making unsustainable choices.

To be sure, neither of the three keys to a less car-intensive world can and will happen in a vacuum. Lifestyle choice, infrastructure, and economic consideration almost always work in tandem, feeding off each other to change the overall trajectory from a car-first to a people-oriented transit Zeitgeist.

Part 3 of this series will take a look at what a future inspired by this kind of a human-scale, integral transportation epoch with no more than 1 billion motorized vehicles globally might look like.

Carsick Planet is a 3-part series excerpted from a photo feature originally published at Medium. All photos by the author, except where noted otherwise.