Each year, Americans generate 389.5 million tons of municipal solid waste, 69 percent of which gets landfilled. As Edward Humes breaks it down in his eye-opening opus Garbology, that’s about 7.1 pounds of garbage per person per day, 365 days a year.

Collectively, Americans generate 18 times the weight of the entire adult population in trash each year.

Individually, each of us is on track to generate 102 TONS of trash across a lifetime.

The waste we create is literally bigger than ourselves.

Looking in the trash mirror on America Recycles Day. Photos by Sven Eberlein.

There are a few municipalities that have done a great job at diverting waste from landfill through composting, recycling and creative reuse of materials, most notably San Francisco’s landmark Zero Waste efforts, which I’ve written about here.

And yet, as a nation, we recycle barely a third of all the material goods that flow through our hands. We trash 40 percent of our food supply every year, valued at $165 billion, the single largest component of solid waste in U.S. landfills. The fact that 97% of all food and food scraps end up in landfills instead of being composted — accounting for almost a fifth of all U.S. methane emissions — is dwarfed only by the sad notion that the wasted food could feed millions of Americans.

While it has become somewhat fashionable to dismiss this garbage crisis as an old-school environmental issue on par with saving the ozone layer, the reality is that the way we deal with the material world is at the root of all the issues deemed more noteworthy, from resource depletion and toxic air & water pollution to environmental justice, soil/food quality, and the biggie, climate change. By dumping, burning, and otherwise taking precious materials out of their natural cycles, we are disrupting the very mechanisms by which life on Earth is made possible.

To put it more bluntly, our buying, consuming and throwing away an ever growing number of industrially produced and packaged things is trashing our own nest.

Which one of these would you like to soon throw away, son?

Throwing away precious resources is not just an environmental issue. In Mississippi, where fewer than one in five people recycle and only around half of residents even have access to a community recycling program in their area, $210 million a year worth of materials is thrown in the garbage and $70 million spent to bury it in landfills. In vast parts of the U.S., even if you would like to treat your used materials with more respect, there’s no infrastructure for it.

A 2011 Ipsos poll found the top barrier to recycling for Americans is it’s not convenient where they live. That’s exacerbated in a rural state like Mississippi, where the nearest bin might be 50 or more miles away.

Clearly, something has gone awry in the modern American mindset that we would not only accept this glaring imbalance on our ecological spreadsheet but choose to throw away billions of dollars worth of precious materials.

So you’re going to bury these in a big hole in the ground. Really?

The question is, why would we do something as irrational as trashing the planet and missing a great opportunity to boost the economy?

The answer, luckily, is not as complex as one might think.

In Mississippi, the two biggest obstacles are access and education — and it’s not at all clear which is the chicken and which is the egg.

In other words:

- Chicken: People don’t recycle and compost because there’s no infrastructure that makes it easy to do so.

- Egg: There’s no recycling and composting infrastructure because people don’t understand the benefits of it and thus there’s no demand.

As so often with these dilemmas, it’s hardly ever one or the other, but usually a little bit of both. In this case, it’s probably fair to say that a good municipal recycling and composting program goes a long way in creating a citizenry that recycles and composts, just as a public that’s educated about waste issues is more likely to lobby their representatives for better recycling facilities.

No matter how far a city or region has come in their resource recovery efforts, making a serious move towards zero waste on a broad national and international scale can only be accomplished if a new generation of citizens can learn to internalize the consciousness and habits required to keep valuable materials out of landfills and incinerators.

America Recycles Day is one such learning opportunity, as I witnessed first hand at Davis Street Resource Complex in San Leandro, CA a couple of weeks ago.

Below are a few impressions from that day. May they shed some light on how more Americans might be led to proclaim:

How I Learned to Stop Wasting and Love the Trash

When I arrived via bike and BART at the Davis Street Transfer Station on the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay, the activities were already in full swing. My first stop was a table where little ones got to stick their hands in soil made from urban compost…

and plant seeds in recycled egg carton planter boxes. There’s nothing more powerful than to feel with your own hands the magic of mother Earth in replenishing itself, and this boy found himself fully immersed in the connection between the food on his plate he didn’t finish and the food that will once again be on his plate.

The next stop was a playful demonstration of the system by which most resources can be recovered. In SF we call it the Fantastic Three and it’s helped the city to keep 80% of discarded stuff out of the landfill. It’s the ABC of resource recovery, and this girl was about to learn how easy it is to turn her lunchbox into new and useful things.

The paper container goes into the blue recycling bin…

The fruit gets tossed into the green composting bin (and so would the paper plate if it had food on it)…

and the potato chips bag, alas, must go in the black landfill. (Several layers of different plastic and polymers are the nemesis of zero waste. However, if you just can’t lay off the salty snacks, check out Terracycle’s Snack Bag Brigade program)…

At the next table another R — Reuse — was in full display. In this case, old CDs. As most of us are moving towards mp3s on our electronic devices, many of the old CD collections are suddenly landfill-bound. While CDs can actually be recycled if you’re lucky enough that your local garbage resource recovery company accepts them, creative reuse is always the preferable option. In this case, the kids learned how to make hanging ornaments out of them

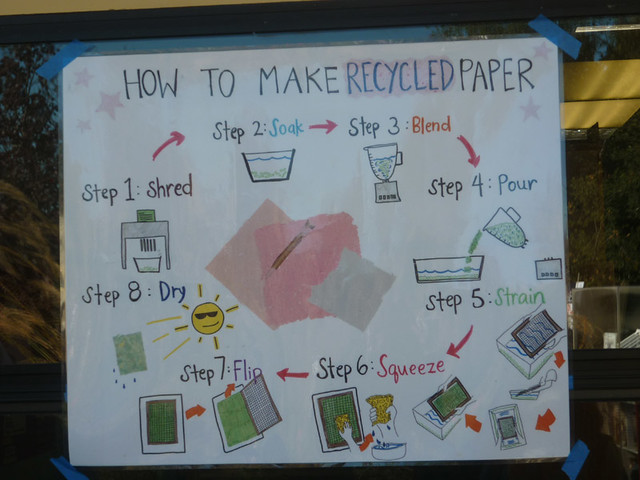

The next stop was really cool, because it showed the completion of the cycle, or rather, the process of getting there. Paper is by far the most recycled resource in America, so we may as well understand how it works. Not surprisingly, it involves a press.

But the whole process is as easy as 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8

Next, I took a trip to the beginning of the cycle, the manufacturing process. I’ve written in-depth about Gary Barker and his ingenious Ditto cardboard hangers, so I won’t go into great detail here. Let’s just say Gary is very passionate about preaching the gospel of manufacturers’ responsibility and educating people about the power they have as consumers to make the right choices.

What Gary will explain to anyone willing to listen (and often those who aren’t) is that each year, 8 BILLION plastic, wire and wood hangers are landfilled in the United States, creating a trash pile the size of 4.6 Empire State Buildings.

It’s hard to believe that in a country that prides itself in being innovative, the wire hanger, that most common of household products, has been an uninspiring staple for over 100 years. Even if it weren’t causing such huge problems at recycling facilities — where it twists into and fouls up the drums that separate different materials — it would still be one boring and ugly thing to put in your closet.

Plastic hangers aren’t much prettier, and they aren’t recyclable and take over a thousand years to break down. Worldwide, 36 BILLION plastic retail hangers alone, or another 20 Empire State Buildings, are landfilled every year by way of the Garments on Hangers (GOH) process that has overseas clothing manufacturers ship garments to stores that are already on plastic hangers. It’s just not the kind of idea smart and caring ancestors would come up with.

Cardboard hangers, by contrast, can simply be tossed in the paper recycling bin, or if your city has a composting program, in the compost bin. And for super bonus points, they can be designed into pretty hip-looking eye candy, as Gary demonstrated with his latest creation.

Speaking of plastic, the woman at the next table was demonstrating how plastic recycling works, shredding and melting the various polymers to manufacture new products.

A word of caution about plastic recycling: It’s true that you can turn this…

into this…

and that’s better than throwing the plastic bottles into the landfill. However, it’s important to understand that the socks, carpets, and lawn chairs that are made out of recycled bottles are the end of the line, because the lower grade plastic that results from mixing the different types of polymers used in bottles cannot be recycled again. So what this should really be called is downcycling, and the best we can hope for with plastic is a bit of a delay in its inevitable trip to the dump, incinerator, or unfortunately all too often, the open ocean.

The woman acknowledged this, and we both agreed that the ideal solution would be not to use as many single-use plastic containers in the first place. Understanding and internalizing these kinds of details is one of the important things that happens to people who are learning to stop wasting and love their trash. Once you dig a little deeper, you realize that life without plastic is entirely possible.

Which brings me to the most efficient and net-positive recyclers in the world — little critters. The last stop gave insight into the lives of these natural decomposers, from worms and slugs to mites and mold. This particular bin showed how to make worms very happy and in exchange break down organic matter and keep feeding nutrients back into the cycle. All it takes is the right mix of shredded paper, food waste, and water, and voila, you’ve got yourself a rich organic fertilizer to grow your own food with.

It may sound odd, but it’s these tiniest members of our cosmic home that have the most to teach us about how to live sustainably within the closed loops of Mama Earth’s ecosystem. And there are already a lot of examples out there of how to make products that use these natural principles. As I wrote in From Soap to Cities, Designing From Nature Could Solve Our Biggest Challenges, fields of inquiry like Cradle to Cradle and Biomimicry that are consciously emulating life’s genius are ready for prime time. Ecovative Design is showing how mushrooms can help us get rid of styrofoam.

It’s really not that complicated. The solutions are far less complex than the industrial masters who’ve been profiting from an extraction economy would have us believe. All the solutions on how to live in balance with nature are provided by nature herself. But to recognize those solutions, we have to open our eyes and be radically curious. What we need is inquiring minds from all walks of life to reconnect us with what’s already there, and the threads the people on both sides of these exhibits were weaving showed that we can rebuild the only web that can sustain all living beings.